by Bill Cunningham

Ted invited me to expand on a comment I made here on how the case can be made for rethinking the design standard for movie poster artwork in order to maximize the visual value to today’s audience, considering a film will likely be discovered online. What I’m proposing is taking the movie poster and turning it on its side, filling our view on the screen and our heads with storytelling potential. Not so much a radical rethink of key art design, but the next step in what has been an evolutionary process tied to distribution. People do judge a movie by its poster, and if independent filmmakers and distributors are to maximize their resources without maximizing costs, then the role and design of key art is definitely in order.

THE ROLE OF THE MOVIE POSTER

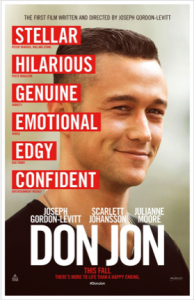

A picture is worth a thousand words, but a (good) movie poster ignites a thousand ideas – an expression of both art and commercial intent, selling the movie to the audience. It does this through craft, style, technique and marketing – ballyhoo made manifest. This is why key art is important, especially to the indie, because if it makes a positive impression, it means the potential for financial as well as artistic success. The better your key art, the lower the sales resistance.

THE TRADITIONAL MOVIE POSTER / KEY ART

It’s important that we understand the basics of what we call the movie poster. The standard movie poster has become a vertical 27” x 40” design originally made to fit inside a theater’s display. [This ignores lobby cards, window cards, the insert, the half-sheet, and the 3 and 6-sheets as well as the European and Asian anomalies.

It’s important that we understand the basics of what we call the movie poster. The standard movie poster has become a vertical 27” x 40” design originally made to fit inside a theater’s display. [This ignores lobby cards, window cards, the insert, the half-sheet, and the 3 and 6-sheets as well as the European and Asian anomalies.

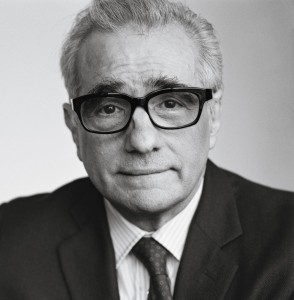

In Adventures in the Screentrade, William Goldman famously opined that “nobody knows anything” in Hollywood, a curious concession for a man with such a marked record of success. The truth, though, is that Hollywood has always known something — its very business centered not just on creating hits but also on predicting future ones.

In Adventures in the Screentrade, William Goldman famously opined that “nobody knows anything” in Hollywood, a curious concession for a man with such a marked record of success. The truth, though, is that Hollywood has always known something — its very business centered not just on creating hits but also on predicting future ones.