By Colin Brown

Politicians go medieval on them, romantic couples break up over them and artistic types tend to run as far and fast as they can from them. And yet budgets, if drawn up sensibly in a spirit of mutual trust rather than defensive hostility, can actually go a long way towards avoiding such heartaches and fistfights. Cinema is certainly no exception here. No matter whether you view filmmaking as primarily a left-brain or a right-brain undertaking, as an expression of exquisite method or inspired madness, there is still no getting round the need for a proper fiscal reckoning. Persuading people to put money behind a particular film idea is, after all, an exercise in quantifying delight. Sooner or later, even with the most munificent of patrons and the most sublime of screenplay propositions, budget numbers still have to be part of that pitch. Get those projections askew and that dream project is a brawl-in-waiting. Get them horribly wrong and it’s a complete non-starter.

Realism over Optimism

While all this might seem like decrees from the department of the bleeding obvious, it is still a lesson in financial realism that seems lost on too many filmmaking novices. Judging by a number of crowd-donation campaigns, there are those who firmly believe they should make their movie with whatever funds they can raise. And they do so without even a basic understanding about who will come to see their finished film – and why – other than those few thousands who volunteer their ten bucks online.

In the real world of actual investment, of course, potential financiers soon lose patience with producers who don’t have a clear picture of how much they will need, and where that money is going. Nor are they impressed by optimistic finance plans based on unrealistic notions of what projects might summon in terms of either talent or contributions from soft money sources, production off-sets and distributor pre-sales.

“Maybe the biggest mistake we see from first-time producers is they come in with too-high budgets. You can see a $5 million or $10 million budget for a project that should cost $1 million or lower,” observed Daniel Baur, partner and producer at the German film finance and sales outfit K5 Media Group, as part of a revealing article last year in Screen International on the keys to unlocking film finance. Battle-tested executives will tell you that nothing resonates more with financiers than the confidence to be honest about a film’s likely costs and commercial prospects – even if those budget estimates fall on the bleak side. Earn that trust and chances are that investors will work with, rather than against, producers in establishing the most comfortable financial parameters for any given story. Regardless of how small the chosen audience niche.

The Equation is not Simple Subtraction

This is essentially what packaging agents and studio executives mean when they talk about the need to make films “for a price.” As it happens, coming up with this magic figure is never quite as straightforward as slashing costs. If it was, and financiers started making projects simply because they are the cheapest on the market, then a depressingly narrow range of copycat projects would be the only ones to ever see the light. As filmmaker John Sayles has wryly noted: “The ideal low-budget movie is set in the present, with few sets, lots of interiors, only a couple speaking actors (none of them known), no major optional effects, no horses to feed. It’s no wonder so many beginning movie-makers set a bunch of not-yet-in-the-Guild teenagers loose in an old house and have some guy in a hockey mask go around and skewer them.”

The fact that Sayles was writing this back in 1987, in his seminal book “Thinking in Pictures”, only underlines how little has changed. Then, as now, there is always room for resourceful films whose stories are designed around their irresistible budgets. But just keeping making such exploitation films, to the exclusion of films whose budgets have been customized to fit their compelling stories, and the film industry will quickly lose the plot.

Budgeting, done properly, is more than just about bottom line numbers; it’s a high-wire balancing act worthy of the most creative dealmakers. As Anthony Kaufman found out when exploring the financing strategies behind the latest visions of Sofia Coppola, James Gray, Alexander Payne and Roman Polanski in his article for Variety this summer. In such auteur-driven cases, the trick is to make the movie for “the absolute lowest price possible without compromising the integrity of the film,” Greg Shapiro, producer of current festival darling THE IMMIGRANT, told him. “This seems a natural and obvious thing to do, but it is usually very difficult in practice. Budgets naturally go up, not down.”

In the end, Shapiro and his producing partners sourced the $16.5 million they needed for their own period piece from a global potpourri of backers, lenders and enablers that included Three Point Capital, Jacob Pechenik’s Venture Forth, Worldview Entertainment, Paris-based Wild Bunch and Chinese billionaire Bruno Wu. Tempting as it might be to now see that $16.5 million as the going rate for all historical dramas, it is only a partial baseline for what the market will bear. Price alone is never the sole factor in greenlighting a film any more than it is in determining how much a film will end up selling for to distributors. The strength of the material and all the other packaging choices that coalesce around that story are just as crucial to those equations.

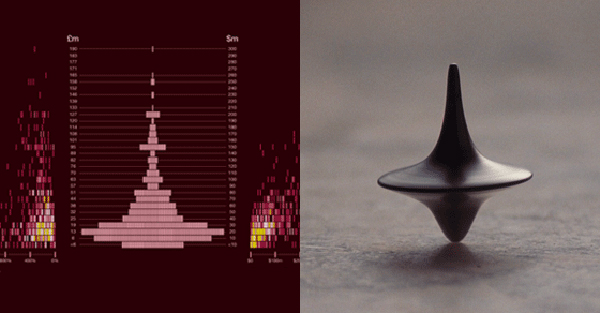

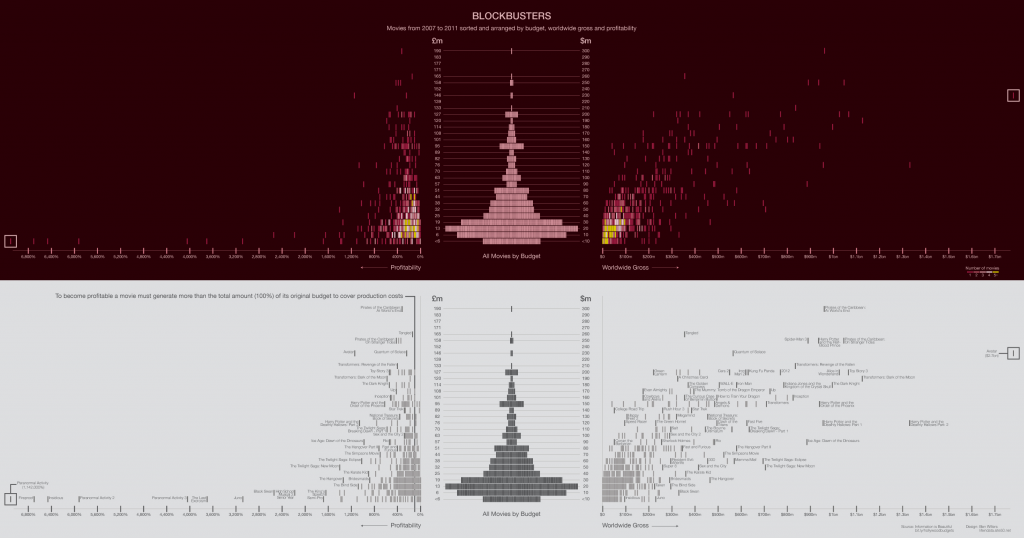

Nonetheless, every film event comes prefaced by sales agents who talk of the latest optimal budgets, preferred genres and the various financial black holes into which no self-respecting project should fall if they want to see their money back. The truth is there has never has been a one-size-fits-all budget sweet spot that is assured of success, nor even different off-the-shelf budgets that are best suited for different genres. While basic data analysis from the last several years of box office returns might suggest that $20 million productions fall in the profitability hot-zone, more rigorous attempts at regression analysis has also gone some way to confirming that no single production budget confers an advantage over any other.

Packaging is Proportionate

In the end, budgeting remains a bespoke sizing exercise that starts with identifying the cornerstone elements of your screenplay and then building a made-to-measure budget around those essential items. You work out what makes a particular project exciting and back into the budget from there using all the data points you can muster concerning prevailing market conditions and available incentives. A carefully crafted budget, as this useful legal overview on film budgeting explains, should serve as guide to prospective participants “that the pieces of the film are proportionate to one another. If each cast member receives tens of millions of dollars, then the look of the film generally should not have home-made special effects.” Remember a good initial budget is not a final accounting, but a professional-looking estimate that should investors and distributors a level of confidence and comfort about the creative allocation of funds.

If any financing rule has withstood the vagaries of the independent marketplace it is that less is more. Which is why the low-budget agreements put in place by the various talent guilds to allow pay scales to be adjusted according to different budgets play such a pivotal role in packaging decisions. In theory, at least, big talents are within financial reach of even the most modest projects. Under the SAGIndie “Modified” agreement, for example, theatrical features budgeted at less than $625,000 need only pay actors an upfront $933 a week, with a provision for one or two leads to receive approximately $65,000. Armed with such a name cast, projects in the mid-six range can become a very compelling investment proposition. More so, perhaps, than a film project in the mid seven figures. It pays therefore for filmmakers to keep an open mind about all the belt-tightening adjustments that will be inevitably asked of them. As Gersh packaging agent Jay Cohenadvised in an interview earlier this year: “don’t be married to any one version of your film… Everyone is so focused on the budget but there are always people who can give you everything you want for less money with a smart plan and the right prep.”

Creative Efficiency

There is no end of online articles and blogs that celebrate the ingenious ways that independent films have learned to stretch their production dollars. Options include trimming shooting days, merging speaking parts, sprucing up locations, getting the most play out of any expensive set-pieces. But nothing saves money quite as effectively as the experience of seasoned line producers, unit production managers and creative producers who know the battles worth fighting, the union agreements that can be made to work, and all the corners that deserve cutting for the sake of maintaining control. Done judiciously, such alterations will go unnoticed by their intended audiences. Done creatively, they may even enhance what ends up on the screen by the mere fact of forcing an imaginative workaround.

There are enough instances of independent film successes salvaged from studios that had put them into turnaround to know that the exact same stories can be told far more cost-efficiently without any undue artistic sacrifice. It is a point driven home this week by producer Gavin Polone in his latest tell-all piece for Vulture. He got hold of the budgets for two films that looked to the average moviegoer as if they were made for a similar scale. Although tonally different, each had two star lead actors and a cast of secondary players who were well known. Both contained significant action sequences, and they were filmed in the same state under the same incentive program. But the studio film cost about $85 million and the independent film came in at $10 million.

“Size doesn’t matter, efficiency does,” declares Polone who details the many ways a Hollywood budget is “polluted with items that never make it on the screen.” His proposed solution is to co-opt the lean-and-mean philosophy of the independent world, and in particular replace those hefty upfront Hollywood salaries with an open-book profit-based compensation system that would, among other benefits, incentivize producers and directors to limit shooting schedules and push for better deals on everything that goes into the creation of a film.

Investing in the Independent

Whether the independent world has itself attained such levels of enlightenment and transparency is open to question. In their zeal to make films for that “price,” film financiers are not above leading producers on until they cannot possibly afford to say no to a budget that requires those producers to make substantial deferrals of fees and overhead. Shortchanging producers this way not only jeopardizes their livelihoods, it also pushes films into production way too soon in an effort to make collect what fees are on the table. Neither side ends up benefiting in the long haul.

As producer Ted Hope noted, as part of trenchant keynote speech he delivered in London earlier this month, both creators and their benefactors need to take responsibility for changing that dynamic – and proper budgeting plays a crucial part in that re-education process. “We are trained to budget our babies and sell them at market for less than their value, not to guide them down the line so they can generate wealth to carry us into ripe old age. Filmmakers must learn how to budget, schedule, and project revenues for their work across their movies’ entire lifespans.”

Get that right and maybe, just maybe, we might entertain the idea of a more far-sighted budgeting mindset in Washington DC as well.

In next week’s installment on film packaging, filmonomics will look at the key considerations that surround the casting of independent film projects, followed by installments on assessing films by filmmaking teams and financing structures.