We are at in incredible time in our indie film culture. The distinct poles at which is perceived have never been more distant. Great things are getting done. Experiments are happening. And people are sharing. Whew!

Since my initial invite upon viewing his “social” film, Hal Siegal has contributed several times to this blog — and each time opened my mind up. So what if you think you don’t play games. Hal makes a good case of why they are already a part of every filmmakers bag of tricks.

Films are a serious business. Truth, dreams, joy, pain, love, hate. This is the spectrum along which we seek to find our art and our humanity. But we aren’t just the animals that tell stories. We are also the animals that create change. Our stories aren’t changing, but the ways we tell them are.

I

The shoddy video clip above is from LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD, and the game being played is a variant of an old, classic game called Nim.

Call us authors, auteurs, readers, viewers, participants or just “friends”—what we seek, what we have always sought, is engagement. If the images that flicker across the retina do not inspire, if they are only cause without effect, then we as creators—as filmmakers—have failed. But you know this.

III

Nim, although ancient, is still quite fun to play. That is, until you discover that it is a mathematical game. If you know the math, you can’t lose.

Games are many things, but serious is not usually considered to be one of them. We play games because they are fun. Period. Unlike films, games don’t challenge our assumptions, and they don’t make us uncomfortable (except when we lose at them). And yet, if games are fun, then consider: where exactly does the fun happen? Games, like films, are delivered straight to the cerebral cortex. Games and films are ultimately emotional. The mechanics are not really so different.

IIIII

Or vice versa: if you don’t know the math, then you can’t win. This of course is one aspect of the symbolism of the game within the film.

I had mentioned this in a previous post: films are like games we play in our heads. Or as David Mamet succinctly puts it in Bambi Versus Godzilla, the only thing that really matters is creating a desire to know what happens next (I’m paraphrasing). In stories, more often than not, we do this by withholding information for a time. There is another, common name for this in the world of game design: a puzzle. (INCEPTION’S ending was so frustrating to many viewers because it was essentially a puzzle with a missing piece, and this drives people crazy). The point is: games may just provide a framework and opportunity for engagement at a level that was before unreachable via a traditional film.

IIIIIII

It’s merely a coincidence that the video clip above is originally from a film, which is playing on a television, that has been re-recorded with a cheap digital video camera and then uploaded to YouTube.

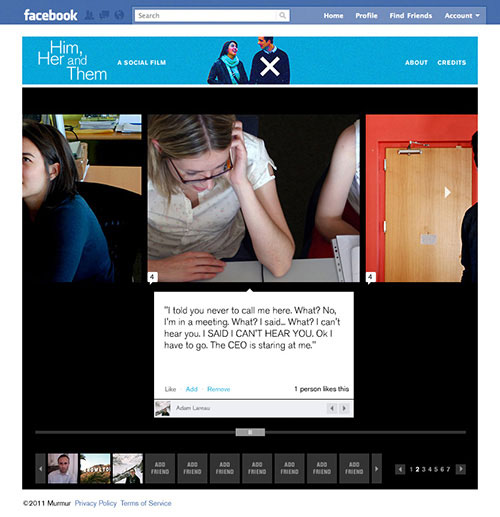

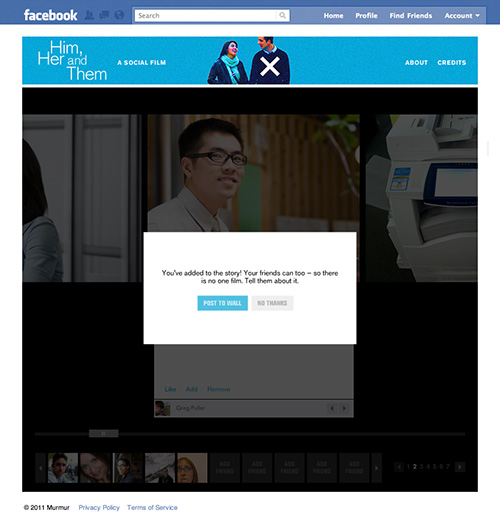

Where to begin then? By acknowledging that films aren’t just going digital. Films are going SOFTWARE. This is the next, inevitable step. Once a film becomes software, there are new opportunities for experimentation and manipulation. Software has inputs and outputs. Software isn’t fixed; it can change over time. As a result, we must rethink the role of the writer and the director: where will you give up control? where are the points of input? Where and how and in what new ways will you engage with your audience? Games already do this.

A suggestion: allow yourself to be inspired by games. However: don’t be intimidated by them. Beg, borrow, and definitely steal from them. But DON’T make games. Keep telling stories. Tell them in new ways.

Hal Siegel is a partner in Murmur, a hybrid studio/technology company that creates and distributes social films. He wrote and directed HIM, HER AND THEM.