Have our filmmakers forgotten how to tap into the subconscious?

When three of the films this past year that do it best are

This is Part 4 of Jon Fougner’s guest series on Cinema Profitablility – today he focuses on the marketing.

Marketing

The last time you went to a movie, how did you decide where to see it? If you’re like most Americans, you simply went to the nearest theater showing it. (Of course, if you’re reading this, you may be a cinephile and therefore a bit more discerning in your choice!) That’s even less brand loyalty than you might show in where you buy commodities like gasoline.

The cinemas have historically deferred to their vendors, typically owned by large media companies, to advertise their products. (Of course, the cinemas have done the crucial re-marketing work of on-site merchandising for the products, in the form of movie trailers, but I doubt that those trailers do much to engender loyalty to the particular cinema (chain) in which they’re shown.) That’s extraordinary; even in verticals where the manufacturers typically buy a lot of media, such as auto, CPG, and QSR, the retailer typically advertises as well, both to complete the bottom of the demand generation funnel and to take share from competing demand fulfillers.

It’s extraordinary, and it may have to change. The good news: many of the needed tactics don’t require paid media. A few are laid out below.

The Big 3 should build low-touch customer relationship management systems anchored by e-mail. A few of the places to capture e-mail addresses from:

• online sales,

• ticket kiosks,

• face-to-face ticket and food sales (when customer lines are not prohibitively long),

• social media,

• and even the studios, whose e-mail lists sometimes go wasted.

Around each e-mail address, build a CRM profile, including:

• first and last name,

• gender,

• home address,

• preferred genres,

• preferred screening times,

• preferred screening days,

• average purchase size,

• price sensitivity (e.g., coupon redemption behavior),

• and viewed trailer history (for data analysis once the advertised film comes out).

Send customers highly-customized e-mails, measuring success by value of tickets sold. (This measurement requires conversion data from the online POS, which should be a show-stopping negotiating demand in any agreement with a 3rd party broker.) Some of the blocking and tackling of optimizing these e-mails is obvious. For instance, the preview field in a major Webmail provider like Gmail shouldn’t tell people to unsubscribe:

And, for instance, no clickable film title (in the screen below, “A Single Man”)…

…should land on a page whose above-the-fold content makes no mention of it:

Some of the fruits hang higher, but tips from entertaining decks like DJ Waldow’s will help spot them. Most of the benefit, however, will come from relentless testing, likely through an e-mail marketing agency. The promotional engine of this CRM system should be a loyalty program. Unlike AMC and Regal, Cinemark doesn’t even appear to have a loyalty program in the U.S.:

The program should leverage game dynamics, such as points collection, leveling up, social status, rewards, and randomization. As CRM gold standard Harrah’s knows, variable positive reinforcement is key. AMC owner Apollo co-owns Harrah’s and could choose to share some of its CRM playbook. The rewards should be meaningful. At a 58% weighted-average gross margin with 90%+ wasted admissions inventory, it’s hard to understand why AMC spends less than 1% of revenues from loyalty customers on their rewards. (For 10 ticket purchases = $83, you get 1 small popcorn, with COGS less than $83 x 1% = $0.83.)

The company’s website will serve several purposes: loyalty program, e-ticketing, gift cards and more. Modeling the value of users’ interactions with these features is the first step towards prioritizing amongst them and optimizing for the highest value conversions while culling all else. Today, if a user visits the Big 3 sites, she’ll experience:

• an emphasis on products rather than her needs,

• clutter,

• irrelevant banner ads,

• text in all capital letters,

• unconventionally small text,

• unconventional hyperlink colors,

• inscrutable text color schemes,

• unconventional background colors,

• links whose landing pages have no apparent correspondence to the link text,

• unclear calls to action,

• search parameters pre-filled to show 0 results,

• altogether empty search results without helpful suggestions,

• overcomplicated registration flows,

• missing standard navigation to home (clickable logo in upper left),

• broken mouse-over ajax interfaces,

• unnecessarily narrowly constrained clickable areas,

• and e-mailed passwords (!).

Experts like SiteTuners.com offer consultation and testing in order to identify and remedy problems like these.

END OF PART Four Tomorrow: Marketing 2 and Margins

— Jon Fougner

Jon leads local product marketing and monetization at Facebook, working with the advertising engineers and product managers to build products for local businesses, ranging from restaurants to movie theaters.

This is Part 3 of Jon Fougner’s guest series on Cinema Profitablility – today he focuses on the channels:

Channels

Do the Big 3 have channel strategies? The vast majority of their tickets are sold either at the box office or via 1 of the 2 online brokers: Comcast’s Fandango with 9mm monthly uniques (used by Regal and Cinemark, plus the legacy business of AMC’s Loews) and AOL-related MovieTickets.com with 3mm monthly uniques (used by AMC ex Loews, plus some legacy business from theaters now owned by Regal). My Gmail is chockobloc of order confirmations from both of these brokers. And yet, I’ve never as a result received targeted e-mail marketing from either of them nor the Big 3 whose inventory (among others) they represent. What a missed opportunity to share anticipated, personal, and relevant marketing! Instead, apparently indifferent to its own brand, Fandango indefatigably pushes irrelevant co-marketing offers (“Get your free credit report and credit score in seconds”), exit pop-ups and all. My inference is that the Big 3 have failed to negotiate an e-mail marketing partnership with their brokers, who, left to their own devices, have strayed off into unsavory lead generation rather than fishing where the (cinephilic) fish are.

This doesn’t make sense. The brokers are in a weak negotiating position, since they need at least to show the Big 3’s showtimes (as they currently do) to appear comprehensive to users. The Big 3 should get out of exclusives with the brokers so they can use them but simultaneously rep their own inventory online, as the airlines do. This would take a bit of SEO, so consumers find their O&O sites when they search on movie titles. The Big 3 tend to invest as consortia, but it’s time for a go-it-alone adventure here.

Website optimization is a separate topic I’ll touch on later, but while on the subject of online ticketing interfaces (whether 3rd party or O&O): there’s no excuse for missing out on free social marketing tools. For instance, implementing Facebook Connect could make it easy for a customer to broadcast his ticket purchase to all his friends, at no cost to the ticketing site. Better yet, when he arrived on the site, he could see which friends were going to which screenings of which movies. Movie-going, after all, is social.

Once a Big 3 player builds its own ticketing site, it should build an affiliate program, giving away most of the service fee as commission. Fandango runs an affiliate program through Commission Junction; its paltry $0.10 per ticket commission pales in comparison to that of leading programs such as Amazon Associates on both a %-of-revenue and a %-of-gross-margin basis, because Fandango knows it has only 1 competitor, whose affiliate program appears to be private. The main partners of such a program would be film sites, the websites of newspapers and local TV news programs, and the long tail of cinephile amateur bloggers. Critics tend to prefer highbrow (think New York Film Festival) and middlebrow (think Oscars) films to mainstream Hollywood fare, so a potential consequence of such a program is the emergence of a viable top-to-bottom marketing funnel whose lack heretofore (along with the expenses of physical prints) accounts for the paucity of “art” films in Big 3 houses.

END OF PART Three Tomorrow: Marketing

— Jon Fougner

Jon leads local product marketing and monetization at Facebook, working with the advertising engineers and product managers to build products for local businesses, ranging from restaurants to movie theaters.

Today’s guest post is Part 2 of Jon Fougner’s guest series on Cinema Profitablility – today he focuses on the products that cinemas offer:

Products

Cinemas’ suppliers have leveraged the proliferation of alternative retailers for their products: DVD, cable, VOD, Netflix, iTunes, Hulu, and more. Cinemas, meanwhile, have barely experimented with sourcing alternative product. The result is an oligopoly5 (the studios) selling to a captive market (the cinemas), a game theoretical nightmare for the buyers, even if they are an oligopoly of their own. That translates to a 55% revenue share back to the studios on tickets. (The other half of gross profit comes from food, sold at an 85% gross margin.) And the theaters know it could get worse, as more films go day-and-date or nearly so.

The good news is that the pending deployment of digital projection will reduce the fixed cost of showing a given product on a given screen to nearly zero. Without having to recoup the cost of manufacturing and shipping a physical print, it’s economically feasible to experiment with niche content that you might exhibit only a few times. Translation: the cinemas can throw scores of more tests against the wall, and arrive at an equilibrium with a greater diversity of content.

Many industry watchers would not have predicted that the digital broadcasting of the Met would have done so well. Let’s try other marquee fine arts (Broadway plays and musicals, ballets, etc.), live sports (Olympics, pro sports, NCAA, etc.), prime-time network TV, other films (classics, independents, etc.), even university lectures. My personal favorite: content with built-in intermissions, so patrons go to concessions during the breaks. Since these productions’ cost structures are already supported by existing revenue streams, and the marginal cost of adding cinema distribution is low, their producers’ negotiating leverage should be low.

Although channel-partnering with cinemas is an obvious win for the Met, since the geographical constraints of its audience means it doesn’t have to fear cannibalization, TV execs might hesitate longer. However, it becomes a no-brainer for even them if the cinemas are willing to show their ads — which makes more sense than relying on National Cinemedia, since the TV ad market enjoys so much more liquidity. Many of these alternative content trials will fail. For instance, competing with sports bars without selling alcohol may be a tough sell. That’s fine. Only keep the winners.

A skeptic might ask: isn’t there a big opportunity cost of borrowing a screen from first-run films to test these alternatives? The Big 3’s screens gross only $44 – $57 / hour (including concessions), or about $100 / hour if you count only noon to midnight. At $7.50 ticket revenue plus $3.50 food revenue per patron, that’s an average of just 20 butts in seats during operating hours (estimating that screenings average two hours apiece). At a wild guess of 200 seats / screen, about 90% of inventory is wasted. During daytime and weekdays, wastage is obviously highest, so these periods are ripest for experimentation. In order to maximize combined profits of the content producers and exhibitors, I suspect that it’s optimal to lower ticket prices for some of this alternative content, since the concessions gross margins are so lucrative. (To do that mental exercise, pretend you are CEO of a holdco that owns both the content developers and the exhibitors, so the content rev share is a wash to your bottom line.) The trouble is, to get to that Pareto-efficient outcome, I bet that the content owners would turn the conversation to revenue-sharing the concessions, which I imagine would make the exhibitors’ heads explode. Rev sharing the concessions is unnecessary to make this work, since there’s so much admissions gross profit being left on the table.

I hope but am led to doubt that each of the Big 3 has built a detailed, quantitative model projecting the total revenue stream of each picture it evaluates for rent. Back in 2006, Malcolm Gladwell was enamored of the team at Epagogix working on this problem. More recently, on the production side, Ryan Kavanaugh has become one of Hollywood’s fastest rising moguls, in large part through his number crunching acumen. (Now even amateur B.O. modelers can put their money where their mouth is, via the “Hollywood Stock Exchange“.) The models are often set up as complex regressions whose right-hand side variables include genre, format, release date, actors, directors, studio marketing budgets, and so on. One risk with such models is that they be over-fit, due to the large number of RHS variables and wealth of historical data. Their analytical approach is typically not experimental, since they don’t have the levers to run the experiments.

Averaging 5,000 screens across 400 cinemas, each Big 3 chain has the luxury of being able to run controlled experiments. For instance, suppose Regal is evaluating two prospective titles, Picture A and Picture B, each of which it projects to gross $20k per screen over its run of April 1 to May 1. It could randomly assign each of its theaters to bid on either A or B, and then look for statistically significant differences in the total revenues of Picture A and Picture B theaters. Besides direct revenue from A and B ticket sales, such an approach would capture indirect effects, such as cannibalization, sell-out spillover, and concessions. (Once most transactions are tied to a specific customer (see below), it will be possible to directly measure such effects: e.g., hypothetically, each “Transformers 3” ticket might generate 1.5x the concessions sales of a “White Ribbon” ticket.) The same experimental design could also be applied to other proposed products, such as new concessions.

So there’s a science here, but there’s also an art — just ask Tim League. His Alamo Drafthouse chain in and around Austin, TX is one of the highest revenue-per-seat cinemas in the United States. Tim has built loyal communities around his theaters, which are the social anchors of their neighborhoods. Revelers pack the house for singalongs, “quote-alongs”, film festivals and more. And they gorge on good food and alcohol. Does it help to be in a college town that’s an anchor of the independent film movement? Of course. Is Tim’s the most profitable theater, per screen, in the country? Maybe not — his costs are high, too. But I’m told that Tim is getting offers to franchise around the country. And if I were one of the Big 3, I’d sweat that.

Assigned seats. Real food. Alcohol. Ticket stub ad inventory for local restaurants’ coupons. Video game tournaments. Subscription products (“Monday Night Comedies”, etc.). Demographic-targeted titles that follow the Netflix rental maps. Ancillary revenue streams akin to how Live Nation makes its gross margin: “VIP” access and film-specific merchandise and media (not necessarily fulfilled on-site). We’ve seen small pilots of some of these. AMC has even promised its lenders some innovations. Which of these products can be meaningfully accretive to margins at scale? We’ll never know, at least not until one of the Big 3 conducts a good ol’ fashioned experiment.

Notes:

5 I say “oligopoly” in the game theoretical, as opposed to legal, sense.

END OF PART Two Tomorrow: Channels

— Jon Fougner

Jon leads local product marketing and monetization at Facebook, working with the advertising engineers and product managers to build products for local businesses, ranging from restaurants to movie theaters.

Jon Reiss wrote to me and suggested this post (which he originally ran on his blog) on how move theaters could experiment more with online and social tools — and build audiences in the process. There’s too much here for anyone interested in the film biz to ever ignore.

We can do better. Let’s get started.

From Jon Reiss:

I had the fortune of meeting Jon Fougner, who is the Principal, Product Marketing Monetization at Facebook at Sundance this year (he was showing filmmakers how best to use Facebook to connect with audiences). He works with the ads engineers and Product Managers to define products that will be successful in the marketplace. I mentioned Think Outside the Box Office and he said «Hey, I wrote this white paper on how movie theaters could be more profitable if they would experiment more, especially with online and social tools. Would you like to take a look at it?» I immediately jumped at the chance to read it and publish it with my good friend Ted Hope. The original is 4000 words – so we have broken it into 5 sections which we will run consecutively through the beginning of next week. Jon will be appearing at the American Pavilion at Cannes on May 13th as well as the Produced By Conference in Los Angeles on June 4th. He’s at facebook.com/jfougner. Note that this draft was written last year; its qualitative and quantitative descriptions of the landscape are still fairly accurate, with at least one key exception: AMC has since revamped their loyalty program.”

Here is Jon’s Post:

Introduction/Abstrac

The role of film exhibition in our imagination dwarfs its role in our economy. Dolby surround sound, residual awe of movie-going as children, proclamations of Hollywood’s sway — all this industrial light and magic create the illusion that movie theaters are a big industry. In fact, cinemas represent only 0.1% of the $14 trillion U.S. GDP. State lotteries rake in 4 times as much. Ticket sales barely outpace inflation, and wispy margins bounce around the single digits. Whether family- or sponsor-owned, their mandate has been to spit off cash.

The result is a space that has attracted an anemic level of innovation, led by three scaled chains: Regal, AMC, and Cinemark. Together, the “Big 3” control 43% of the U.S. market. I say “together” because the three tend to act as consortia and exhibit (no pun intended) parallel behavior. Some adjacent innovation offers hope. For instance, as Avatar demonstrated, the studios’ development of 3D may prove one of several sorely needed silver bullets. But most adjacent innovation — in particular, high-resolution flat screens for home viewing, and Internet-based distribution vehicles to supply them with video — is an existential threat to the cinemas.

I believe that, without innovation, at least 1 of the Big 3 exhibitors risks losing its equity capital2 in the next five years. To be sure, their plight facing looming debt maturities is not as dire as Blockbuster’s. What’s more, there is a lot of low-hanging fruit. What I lay out below is an array of product, channel, marketing, and (in less detail) cost control tactics to get the ball rolling. More important than any one of these tactics, however, is the overall strategic mentality: to think more like a technology company. They need to embrace the scientific method to experiment, analyze, and iterate. They need to distribute to the edges of their employee base permission, responsibility, and incentive for delivering great products (think Starbucks or Nordstrom) and generating new ideas (think Best Buy or Google). And they need to move fast.3

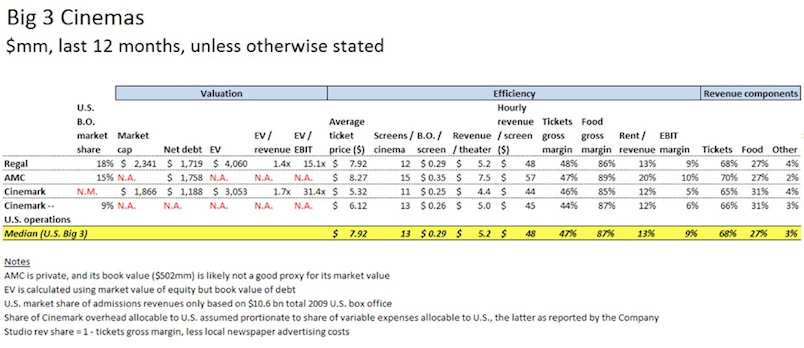

Here’s a summary of where they stand:

Footnotes

1 My employer is Facebook. This article represents my thoughts, not its. Thanks to Zakia Rahman, Colin Darretta, Harry Chotiner, and Jared Gores for providing helpful comments on a draft. The usual disclaimer applies.

2 In the case of Apollo-owned AMC, it’s possible that, instead, value will be transferred from debt holders to equity holders, as was the case with Harrah’s, which Apollo and TPG own.

3 Some of these insights may be applicable to smaller cinema businesses, too.

4 Does not yet reflect 4Q 2009.

END OF PART ONE Tomorrow: Products

— Jon Fougner

Jon leads local product marketing and monetization at Facebook, working with the advertising engineers and product managers to build products for local businesses, ranging from restaurants to movie theaters.