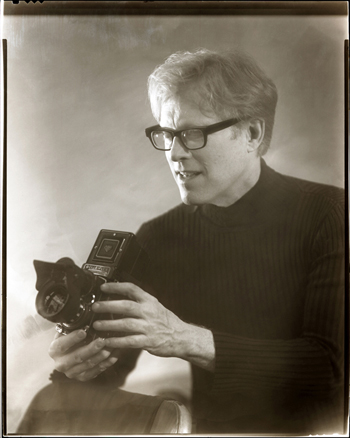

By Audrey Ewell

2012 is going to be the year of truly free filmmaker experimentation. 2012 is going to be the year of cross-platform collaboration. And 2012 is going to be the year of filmmaker to filmmaker collaboration. I don’t know how much of this will be true, but I know I wish all of it will be, and so far, there is no clearer indicator that all will be true than The 99% Film. We’ve heard from Audrey Ewell, one of the film’s collaborators, and we know she always has progressive and provocative ideas, so why should this time be any different. Today Audrey shares with other some of the new ways she and her team are making use of some of the plethora of options that are out there to enable us to truly build it better together.

Crowdfunding a Collaborative Film: Repurposing a Distribution Platform into A New Fundraising Tool.

99% – The Occupy Wall Street Collaborative Film began as a spontaneous project, and thus it began with no funding at all. While it might seem like a poster-child for crowdfunding opportunity, this film actually has some unique obstacles: for starters, many people who support us also support the Occupy Movement, and their spare dollars go straight to them. Our film is not part of OWS; although some of our 75+ filmmakers identify as part of it, we are a separate, independent project, and we receive no Occupy funding.

Additionally, donations to OWS itself dropped off markedly after the first heady days (when it seemed as though time had stopped at the moment in Sidney Lumet’s 1976 film Network when Peter Finch’s Howard Beale led the city in a chorus of “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!” only to resume in reality 35 years later at Zuccotti Park). Plus, with the otherwise lovely Christmas season turning potential funding into slippers and iPads, crowdfunding has been no picnic. We now emerge from the holidays with about two weeks left to hit our goal of $17,500. Two critical weeks, because make no mistake: we need those funds to keep going.

Before I get to the new tool we’re test-driving, let me back up for a second to talk about our overall strategy. First, we put together an outreach team: Stephen Dotson and Kari Collins on Twitter, Laura Alexander on Facebook, Annie Riordan doing direct outreach to influencers and organizations who might help spread the word, Ginger Liu on newswires, blog and social (non fb & twitter) outreach, and me on press releases, blog outreach, and traditional press.

But really, nobody wants to write about your damn Kickstarter campaign, so you have to find ways to make it newsworthy. I set this up as a five-week campaign (with the expected week of Christmas drop-off in the middle). Week one outreach was about the film itself; the collaborative nature and the way our process mirrors OWS got us some press that might be difficult for a more standard doc to achieve.

For week two, Billy Miller (one of our filmmakers, also a curator) gathered our first round of rewards: artworks by 12 contemporary artists. We contacted and posted to hundreds of art blogs. Then we added a fresh round of artists/works (a lot had already been nabbed) and let that slide over Christmas into week 3: when Aaron Aites, my film partner and also the main man behind the band Iran, worked with Kyp Malone (of Iran, TV on the Radio, and Rain Machine) to put together a slew of music rewards. Signed records and artworks from Conor Oberst (Bright Eyes), John Dwyer (Thee Oh Sees), Wayne Coyne (Flaming Lips) and many more fueled a new round of targeted outreach, but still, so much ground to cover by Jan 13th!

So when Darcy at Constellation got in touch to propose a new venture, combining their social screening platform with our Kickstarter campaign, I had to wonder if this might be a peanut butter and chocolate crowdfunding moment. I’d checked out Constellation when they launched; they mix classics (Grey Gardens, Rashomon) with newer and noteworthy indie films (Food Fight, Trouble The Water, Marwencol) and there’s a social element to the screenings: pre-set times to make it a group experience, Q & A’s with filmmakers, and chats with the audience. In their words:

“Constellation is your online movie theater. Just like a traditional theater, users purchase tickets to attend scheduled showtimes of films, or create their own showtimes. However unlike other online platforms, watching movies on Constellation is a social experience. Users can invite friends to showtimes they’re attending and watch together. Many movies are presented by VIP hosts, such as the films’ directors, actors, or other notables, who appear live in the online theater to answer questions from the audience during and after the film. “

So Constellation’s interested in working with Kickstarter (and presumably other crowdfunding sites) projects, and we’re interested in reaching our goal; we agreed to be the first to try it out. Although reluctant to divert our attention while in the thick of making the film, we think there’s a place for this in our fundraising strategy.

So this January 7th at 7:30 pm EST we’re holding a screening of 45 minutes of footage that’s been shot for our film, on Constellation.TV. It’s not a work-in-progress, and Constellation have been respectful of our need to not use that language, but it is a chance for our backers and others to see some of the material we’re working with, and to talk to us as we’re shaping the film. (They also let us lower the ticket price, and gave us half-off codes for our Kickstarter backers, plus free codes so all 75 of our filmmakers can be present – woo-hoo!) It’s a chance for us to get some feedback, build our audience, and possibly even meet new backers.

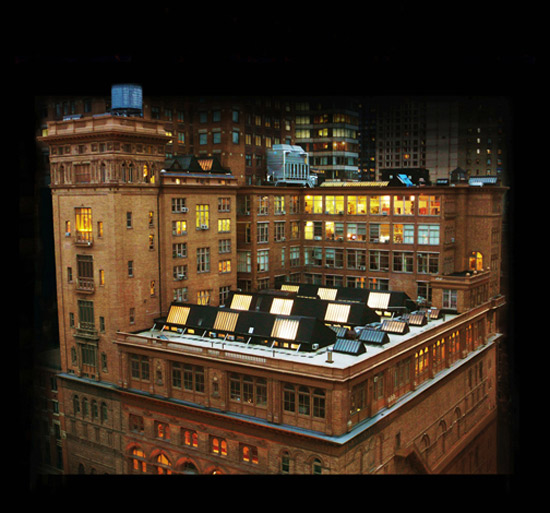

I don’t know how well this platform is working for finished films, but that also depends on each filmmaker’s goal with it (as with any distribution outlet). But it’s good to know that Constellation is open to this sort of fundraising event. I learned, while theatrically distributing my last film, Until The Light Takes Us, that event-izing really helps. So if you’re interested, this is the direct link to the screening: www.constellation.tv/99percent. Or if you need a reminder like I do, here is the Facebook invite. (Oh! And proceeds go toward our Kickstarter campaign!)

If this is successful, it could be a new tool in the indie filmmaker’s funding kit. So wish us luck; better yet, check out the screening, ask questions, and by all means, please invite a friend.

Audrey Ewell is a filmmaker living in Brooklyn, NY with her film partner Aaron Aites. They recently made the award-winning film Until The Light Takes Us, and they’re now working on a thriller called Dark Places. The 99% Kickstarter page is here.