Some subjects are truly difficult to confront on film, both from a personal and public perspective. Creativity generally requires confrontations — with oneself, others, and the world at large. Those of us who indulge in these battles, recognize that we — and our work — are better for it. Personally speaking, I think it even extends much further: our culture and our world are better for it too. But that doesn’t make it easy.

What does make it very satisfying, is to be able to stand back after it all, and recognize that the initial decision, the one to engage, was not just justified, but ours. It is that decision that makes a movie our movie. And it is that decision too, that I think allows a film to speak personally to a veiwer, to help them recognize that this film is not a corporate product, but something truly heartfelt. Writer/Director of THE LEDGE (currently in theaters) Matthew Chapman guests today, and captures that feeling perfectly.

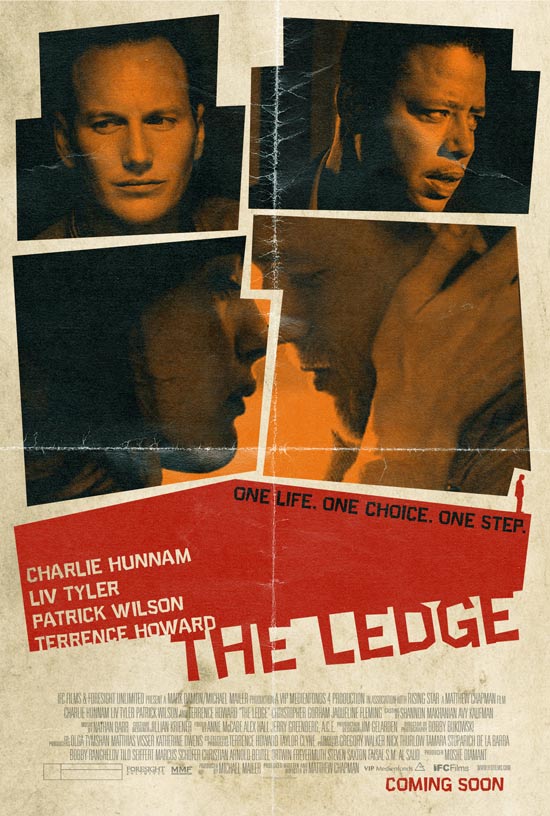

My film, “The Ledge” has been out in theaters for a week, on VOD and iTunes for a little longer. It’s the story of an atheist forced to choose between his own life and someone else’s. It’s a a suspenseful thriller with an internal debate that’s pissed off a lot of people, among them Bill Donohue of The Catholic League. It’s the first film I’ve made in 20 years, and here are some of my thoughts about coming back.

I took my daughter on a ghost train. When it finished, she said, “That was horrible – let’s go again.” This is how I feel about making movies. After forty or fifty long hard days in a row, you say to yourself, “I can’t wait for this to end.” A few days later, you start thinking, “I want to go back and this time do it right.” I stopped directing twenty years ago. I wanted to see my child’s first year of life and knew if I was directing I wouldn’t. I fell into a lucrative groove as a screenwriter and came back to directing only when she was grown up. I look at my movies from before this paternity leave and see the work of a stranger.

By 2008, I’d written two well-received non-fiction books and enjoyed a simple and direct relationship with two literary editors. When it came to writing screenplays, things became harder. No one in the development process was exactly wrong, but they couldn’t all be right. Taking notes from so many people flattened everything. For every risk I took with character, someone would say, “But I’d never do that.” “Quite likely so,” I’d think, “but I would.” Characters became less interesting, so plot became less interesting. I generalize, of course; I had many happy creative relationships, in and out of the studio system, but they occurred despite the system rather than because of it: someone was brave enough to take charge – a strong producer, director, or executive. But as the studios made more tent poles, there was less work and confidence and courage became rarer.

A good script of mine became such a bad movie I took a plane to Belem at the mouth of the Amazon, got on a boat, and headed upriver to avoid the shit I knew would undeservedly fly my way when it opened. One day in a hammock watching Manaus go by, I decided to go back to directing. I was proud of my books, but not of my movies. From now on, if anyone was going to fuck up my writing, I’d fuck it up myself. As much as possible I’d do it on my own terms: for a start, I’d write a script that most likely no one would make because it would reflect who I am (a member of one of the most reviled minorities in America), but I’d enjoy writing it, and if it failed to come alive as a movie, I could at least say, as I could say of my two books, “This is mine.” I realize that to admit defeat before you start is not the American way, but it was liberating.

A poll of American voters found that while 72% would consider voting for a Mormon presidential candidate, 55% for a gay candidate, only 45% (the lowest score out of all the categories) would consider voting for an atheist. Why you’d vote for someone who is credulous enough to believe the peculiarities of the Mormon faith, but feel uneasy about someone who simply requires a little proof before believing stuff seems strange to me, but then I am an atheist.

I decided to write a film about an atheist who comes in conflict with a fundamentalist with dire consequences. I wrote it in a form I’m comfortable with, the thriller. The story was stimulated by research trips I’d made for my books. These journeys were in large part explorations of the religious gut of America, forays into heartland beliefs. The fundamentalist (played by Patrick Wilson), is a man I have met many, many times. You don’t find him much in LA or New York, but you find him everywhere else. He’ll tell you that eight ninths of the world’s population, over five billion people, are going to burn in hell for all eternity and that you’re one of them – then he’ll smile pleasantly and ask if you’d like another cup of coffee. Spectacular acceptance of spectacular violence. His wife (played by Liv Tyler) is based on a woman I met in Tennessee who’d taken some beatings, sought comfort in a protective religious marriage, but now found it oppressive. The cop who tries to talk Charlie’s character off the titular ledge is a cross between a New York man and my father, who, like Terrence’s character, raised a child of adultery. The atheist (played by Charlie Hunnam) is based on me. His philosophical views, his past suffering, his mixture of insolence and (I like to think) charm are me. Charlie’s gay room mate (played by Christopher Gorham) is an amalgam of my uncle and his male partner who have been together for five decades and were the best example of a relationship that existed in my childhood. (The film is dedicated to them.)

Accepting defeat from the start, I wrote what I wanted. An often obnoxious, overly seductive atheist? Great! Seven pages of dialogue about faith? Fuck it, why not? An unpopular philosophical viewpoint? An unhappy ending? Who cares, no one was going to see it anyhow.

When the script was finished, it was good enough to attract two wonderful producers and the above actors, and to my great surprise, I suddenly found myself back on the ghost train. After a short but exhausting shoot, I was glad to step off. But now that it’s over, I already want to get back on. I had a wonderful cinematographer, Bobby Bukowski. All the actors were great. Liv Tyler is a revelation: her performance is the birth of a woman cinema actor who will go on working for as long as she wants. Patrick Wilson is, as always, brilliant. In my view he’ll eventually be judged one of America’s enduring greats. Terrence is marvelous. So is Charlie. The film was selected for Sundance to compete in Best US Drama.

In all the screenings I’ve been to, I’ve never seen anyone walk out of the theater except to go to the bathroom. I’ve had emails from people who have changed their views because of the movie. There have been reconciliations between believers and their gay relatives. Atheists from across America have written to thank me and spoken of what it’s like to be a non-believer in America, how hard it is to come out of the closet in communities dominated by religion. Women have written to say how they have been married to men like Joe, the fundamentalist, and how inspiring Liv’s character is to them. A mention of the film on CNN.com engendered over 5000 comments, atheists and believers debating faith. This was so unusual, I was asked to go on CNN myself to talk about atheism and “The Ledge”.

But mainstream critics have largely been in agreement with Bill Donohue of the Catholic League, and not liked the film. I expected this. If 4% of Americans are atheist that means 96% are not and 84% are definitively not! The film does not just attack Christianity, it attacks the whole concept of faith. These are sensitive matters and there’s no reason to imagine critics defy religious statistics to any great degree. Much of their and Bill Donohue’s criticism is focused on the character of Joe, the fundamentalist in my movie. Many of the critics could not believe in a character with such extreme religious views. I know from personal experience (backed up by many comments and emails from people who live away from the coasts and know many people like Joe) that this criticism is just ignorance. Statistics about the Old Testament bent of Christianity in America clearly show that men like Joe are terrifyingly common. Coastal snobbery relegates them to the powerless, irrelevant category of “white trash”, a cartoonish sub-species therefore less real, therefore less frightening. When someone from this category is then portrayed, he is, by circular logic, “cartoonish”, unreal, unbelievable. Of course, few people go around the interior of America asking people what they believe and how fervently. Because of my two books – both dealing with the battle between faith and science – I have done this, and what I found was that people like Joe are not white trash, they’re very human, very wounded, and often very intelligent.

The irony of the release of “The Ledge” is that it is opening theatrically in the two cities in America least likely to appreciate or benefit from it. Religion is not a great force in New York or Los Angeles. The towns that would really understand it are the ones in the middle. It’s great that it’s coming out on VOD and via iTunes and Sundance Now. It is from people who live in the middle of the country who have seen it via these other means that I am getting the most passionate responses, but it’s not the same as a theatrical opening where local media are forced to cover it and debates break out outside the movie theater, in the bars, cafes, and churches.

Has negative criticism depressed me? A little. Has the almost unprecedented debate that’s broken out as a result of the movie made me proud? Very much so. Have the positive, often tearful reactions of atheists, agnostics, abused women, gay people, and young people looking for a new way to live given me joy? More than I can express.

If you asked me “Are you happy with the film?” I’d say “Yes.” I shot it in 20 days and only had a day of rehearsal, but, imperfect as it is, “The Ledge” is a pretty true reflection of who I am. It is, as far as anything can be that’s a result of such a collaborative process, mine. This is the beauty of independent film.

The Ledge is now playing at the IFC Center in New York, and at the Sunset 5 in Los Angeles. For further details visit www.ledgemovie.com

BIO: Matthew Chapman has directed several indie films and written or co-written several screenplays including “Consenting Adults” and “Runaway Jury.” He has also written two non-fiction books, “Trials Of The Monkey – An Accidental Memoir,” and “40 Days and 40 Nights – Darwin, Intelligent Design, God, OxyContin, and Other Oddities On Trial In Pennsylvania.” He is the President and co-founder of ScienceDebate.org, an organization trying to get the presidential candidates to hold a debate on science.