I am dismayed at times how sometimes our local indie scene feels so repetitive and lacking creative ambition. We remake successful formulas, and only rarely break new ground. I know I am guilty of this too. I wonder how we can break out of this cycle, and what are the forces that contribute to this sad phenomenon?

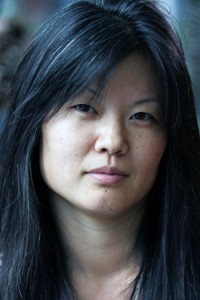

It was such pondering that led me to profess on twitter that I wanted to learn more of the global microbudget film scene, to see what others are doing, and what we all could learn from each other. Producer/distributor Karin Chien was among those that reached out to me, to share her knowledge and experience — and it does start to show us a real alternative.

Let me start by making a provocative statement – in my three years of distributing and working with Chinese independent filmmakers, I’ve experienced greater creative freedom than in ten years of producing independent film in the US.

For most of us, Chinese independent cinema is an unknown. A film like Zhang Yimou’s HERO, financed with Chinese state backing, about Chinese empire, and made by a party-line director, is sold here as arthouse fare, distributed by Miramax. Subtitles are enough to qualify a film as “independent cinema” in America.

So let’s begin with a redefinition. The films I work with are made outside the state studio system and without official government authorization. These are films that do not submit scripts or finished products to censorship committees. These are also films that cannot obtain official distribution or official funding in China. These films are often referred to in the West as unauthorized, underground filmmaking. The Chinese filmmakers call it independent cinema.

So how do you make films outside the system in China? You fly under the radar or work on the margins. Films are made on microbudgets, with cast and crews consisting of friends and family, shot with digital cameras, edited on laptops, and fueled by passion and a singular vision. In their domestic market, most of these films will only be shown at independent film festivals, where filmmakers sometimes hawk DVDs after screenings. Some filmmakers experiment with uploading films onto YouTube, some count on European sales to recoup their budgets, some rely on grants to finance their next films, and some even find angel investors. A tiny percentage will pierce the mainstream consciousness, but all of them will strive to make another film.

Sound familiar?

But here’s where American and Chinese micro-budget cinema diverge. Because we still believe in a one-in-a-Blair-Witch chance, most American indie films willingly play the Hollywood system. The carrot of theatrical distribution and financing motivates even micro-budget films to favor rising stars when casting, adjust scripts for wider audience appeal/product placement/cameos, or tell stories in genres that American and international audiences watch in droves. (As a producer, I’m fully guilty.) In short, commercial considerations influence nearly every aspect of American independent filmmaking, even at the $25,000 budget level. There are those who escape these burdens and make uncompromising films, but they are the exceptions.

In Chinese independent cinema, our exception becomes their rule. When you take the domestic marketplace out of the equation, what becomes the impetus for filmmaking? Not only trained filmmakers but poets, painters, and journalists are turning to digital video as an aesthetic, social, political, or personal tool. Painters like Xu Xin (KARAMAY) and Hu Jie (THOUGH I AM GONE) wield video cameras like a well-honed brush: within the digital image, they are preserving and observing China’s recent history, showing us events that cannot be taught in schools or spoken about on the news. Artists like Huang Weikai (DISORDER) and Zhao Dayong (GHOST TOWN) are making groundbreaking films that rewrite the rules of cinema because they weren’t taught those rules in the first place.

By choosing to work outside the system, Chinese independent filmmakers are shut out of monetized domestic distribution. No theatrical, no TV broadcast, no home video (pirated anyways), no Internet VOD. Here’s a thought: if there was absolutely no chance your film would receive commercial distribution in the US, would you still make your film? What would it look like, and would you cast/write/shoot/edit differently? And if that freed you to take creative risks, would that be irresponsible filmmaking or would it be truly free filmmaking?

I don’t mean to dismiss the very real and very diffuse oppression that Chinese independent filmmakers can face. The temptations of wider audience, greater financing and theatrical distribution are as strong in China as anywhere – they have lured many a filmmaker away from independent filmmaking and into the state studio system. But for those who choose to create independent cinema in China, they have chosen to operate on the margins of a large state apparatus, without guarantees of freedom of speech, freedom of movement, or freedom of production. Yet they have also generated a space that allows for maximum creative freedom. Somehow, in the midst of all this repressive state authority, independent filmmakers are producing the only free media in China. It’s a startling realization.

Given the production parallels to our own micro-budget filmmaking, it’s hard not to extrapolate the comparison. In the US, where capitalism long ago co-opted the language of independent film (see Warner Independent Pictures), it’s a small miracle that any film is made outside the Hollywood system. Anyone who’s ever tried to cast a film with professional actors can attest to this. Perhaps in China, because the machinery is so clearly labeled STATE, it’s a more visible force. Here, the multi-national corporate apparatus is omnipresent.

For the last three years, my dGenerate Films partners and I have been distributing Chinese independent cinema around the world, mainly in the US. We send revenue to independent filmmakers in China every fiscal quarter, and that feels good.

But our revenue is small compared to what filmmakers receive from European distributors. The greater international film community has set up shop in Beijing so they can catch these films first. American industry and audiences would do well to pay as much attention. We will not only learn something about China, but perhaps also about creative freedom in independent filmmaking.

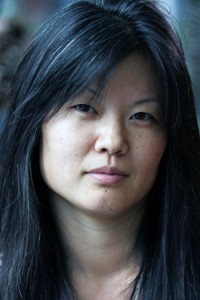

— Karin Chien

Ted’s Note: The New York Times got in on this discussion with a great article on how local Chinese filmmakers navigate the system over there. Kim Voynar at MovieCityNews took the conversation in another direction looking at how some of Karin’s questions have resonated here in the US in filmmakers work.

Karin Chien is an independent film producer based in New York City, the recipient of the 2010 Independent Spirit Producers Award, and producer of eight feature-length films, including CIRCUMSTANCE (2011), THE EXPLODING GIRL (2009), THE MOTEL (2005), and ROBOT STORIES (2002) which have won over 100 festival awards and received international distribution. Karin is also the president and founder of dGenerate Films, the leading distributor of independent Chinese cinema to North America and beyond.