By Charles Peirce

Originating in the thinking of Plato but finding its modern applications from the work of Carl Jung, Archetype Theory is a way of looking at and defining the world that has numerous uses, particularly in marketing and storytelling. At the least, Archetype Theory gives a structural thematic underpinning to organize ideas around. At the greatest, Archetype Theory might allow a primal, subconscious form of resonance and communication with audiences — speaking to them beyond the limits of language.

Originating in the thinking of Plato but finding its modern applications from the work of Carl Jung, Archetype Theory is a way of looking at and defining the world that has numerous uses, particularly in marketing and storytelling. At the least, Archetype Theory gives a structural thematic underpinning to organize ideas around. At the greatest, Archetype Theory might allow a primal, subconscious form of resonance and communication with audiences — speaking to them beyond the limits of language.

For Plato, there were ideal “Forms” — perfect structures of thoughts and ideas which could never exist in practical reality but which were the basis of what we experience and create. Jung expounded on this idea with that of “Archetypes”, what he described as the “contents of the collective unconscious.” Archetypes were forms that represented a common psychic structure for humanity, one not based on personal experience but which still created a continuing psychological continuity for human history. These Archetypes were necessarily primal, mercurial, and omni-present — such that their influence was impossible to escape (or not be formed by).

In a sense, Archetypes represent the core building blocks of reality as experienced by consciousness. While not actually tangible, realized things in the practical sense, they are a categorical structuring of the unconscious which manifests itself in any creative work. Story tropes of all kinds — from naive peasants becoming great heroes (or scullery maids into princesses) to old wise men with hidden wisdom to apocalyptic floods or fearsome descents into caves — are considered to be archetypal patterns, repeating, changing form but often not content, necessary to our development both personally and culturally.

The practical application of Archetype Theory should be obvious: by being aware of the archetypal patterns within your work, you can make sure that you both clearly define and differentiate your stories via them. While there might be multiple archetypal characters in your story, at its core it is most likely about one specific archetype (usually that of the main protagonist). Understanding that, and focusing your story there, will allow your work to speak on a more direct level with the subconscious itself.

The basic Jungian archetypes are the foundation of personal identity, manifested outwardly: The Wise Old Man (high instincts), the Animal (base instincts), The Shadow (divided self, antithesis, the forbidden), The Anima (for men, the primal female image), Animus (for women, the primal male image), Mother, Child. For storytelling, marketing, branding, etc, we tend to concentrate on a larger, more generic and more mythically-oriented group of archetypes: [1]

BASIC ARCHETYPES

- INNOCENT: The Innocent is the naive and childlike quality in everything, which often demonstrates our loss of that very state. Stories centered around innocents sometimes present worlds that are anything but. Stories are usually about faith, nostalgia, and the desire for a return to a more primal, perfect state of being.

Examples: Forrest Gump, Wall E - HERO: The basic aspirational narrative for greatness through personal achievement. While we tend to think of our hero stories as positive in nature, they can equally be about a downfall or the attainment of base and worldly desires.

Examples: Lord of the Rings, Hunger Games, Zero Dark Thirty - OUTLAW: The counterpoint to the Hero archetype, frequently containing the seeds of the same story. Whereas the Hero is usually aligned with what we recognize as the important values of the world, the Outlaw is often in stark opposition to the world as it exists.

Examples: Batman, Breaking Bad, Orange is the New Black - MAGICIAN: Magician stories are about personal transformation, embracing alternative wisdoms and teachings, and the ability for the world to be changed by magic or faith.

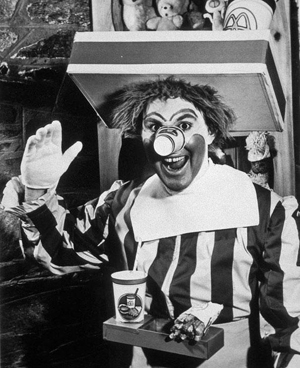

Examples: Harry Potter - TRICKSTER: Narratives that center on playfulness, the desire for happiness, and the deceptive power of laughter in the face of conflict. The Trickster is one of the big cultural archetypes throughout history and usually evolves over time from being a basic troublemaker to a great hero who overthrows the existing order.

Examples: Pirates of the Carribbean, The Hangover - EVERYMAN: Everyman narratives focus on the desire to fit in, be normal, and find belonging, but also its opposite: when the everyday is a mask for something hidden or unknown.

Examples: The Bourne Identity, Good Will Hunting, The Talented Mr Ripley, (ie, just about everything Matt Damon has been in). - LOVER: Stories about finding love, intimacy, and connection — romances of all kinds.

Examples: Her, Before Midnight, most Romantic comedies. - CAREGIVER: Stories about protection, safety, and caring for others. While classically associated with the idea of Motherhood, quite a few recent movies have been placing the Caregiver archetype in less obvious, masculine forms (perhaps a complementary movement to Hero narratives that focus on female protagonists).

Examples: Twilight, Taken - RULER: Narratives about power and control, focusing on the qualities that requires or the worlds where those concerns dominate.

Examples: Game of Thrones, House of Cards - EXPLORER: Stories about finding yourself through discovering the outside world.

Examples: Many documentaries fall under this Archetype. - CREATOR: Stories about creating something, realizing vision, building new worlds.

Examples: The Lego Movie - SAGE: Stories about discovering truth.

Examples: Legal movies, detective movies, mysteries.

A great deal of movies deal with one primal archetype being transformed into another (say an Innocent or Everyman being transformed into a Hero, or a Ruler into an Outlaw). That said, individual archetypes are neither inherently positive or negative, and our relationship to them — both individually and culturally as a whole, can be quite dynamic and convoluted. A common wisdom, however, is that their absence often represents a need for their presence, and it is at those times that they re-emerge in the popular culture in often new or disguised forms (say for instance, Twilight and 50 Shades of Grey as manifestations of the masculine form of the Caregiver archetype).

Films and stories of all kinds have a great advantage over other media when it comes to the use of Archetypes — since they are a way to define stories symbolically, they’re inherently already within any narrative. It’s just a matter of figuring out what those Archetypes are and how best to communicate their presence to an audience. In contrast, Brands often have to create a narrative around themselves, aligning it with an Archetype, and then individuating themselves in the public sphere against competition that might be using the same archetype.

Notes

1. Jung doesn’t categorize Archetypes in this specific way, being concerned with their more pure and primal core and seeing them as capable of manifesting in a variety of forms, mythic and otherwise. This list is primarly culled from The Hero and The Outlaw by Margaret Mark and Carol S Pearson, which is a great work for anybody who is interested in Archetype Theory and its direct relationship to marketing and branding. People who are specifically interested in Archetypes from a storytelling perspective should start at Joseph Campbell and Jung’s Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious.

Previously: Principles of Strategy

Next Week: Casting, Celebrities, and Archetype Theory

Nobody Knows Anything is a speculative journey through the more esoteric theories of popular culture: what that means, what comes next, and what can be done about it.

Charles Peirce is a screenwriter and musician, with an active interest in marketing, behavorial psychology and strategy. He finds it odd to talk about himself in the third person. He can be reached at ctcpeirce@gmail.com or via twitter @ctcpeirce.