By Charles Peirce

Casting is one of the obvious essentials of any film, and like all aspects of the process worth examining: the assumptions that define it and the possibilities of how it might be used to best advantage. Casting’s key place comes in financing, where attaching the right star allows raising money based on their monetary value to specific regions or demographics. Enough attached stars offer the promise of pre-sales in distribution, and enough pre-sales can then determine a base budget. This would seem to follow the simple logic of a star’s popularity guaranteeing viewers, a shortcut in the task of finding an audience. It is an idea that continues from the Studio System legacy and still exists in many people’s mind as the inviolable component that determines a film’s success. [1]

Casting is one of the obvious essentials of any film, and like all aspects of the process worth examining: the assumptions that define it and the possibilities of how it might be used to best advantage. Casting’s key place comes in financing, where attaching the right star allows raising money based on their monetary value to specific regions or demographics. Enough attached stars offer the promise of pre-sales in distribution, and enough pre-sales can then determine a base budget. This would seem to follow the simple logic of a star’s popularity guaranteeing viewers, a shortcut in the task of finding an audience. It is an idea that continues from the Studio System legacy and still exists in many people’s mind as the inviolable component that determines a film’s success. [1]

That stars bring with them an audience is without question: whether that audience is willing to watch them in a particular film — or enjoy them in that film — is an often ignored element of this. Stars have an audience, but like anything, it is a specific audience, with its own needs, desires, and interests. You can see the disconnect between a star’s audience and their potential value in a film most obviously in obsessions with social media metrics, where a huge fanbase represents scale but not depth. Just because you have one does not mean you have the other.

There is some semblance of a science to celebrity and how their presence or endorsement effects other cultural products. [2] It comes from Communication Theory and involves how meaning is transferred from one object to another. Concerns over perceived appropriateness, trustworthiness, and expertise all influence this, but even metrics that touch on this (say those used by Netflix to determine their casting) would stand to have a better way to define a star and their audience. Which brings us to the question — what is celebrity and why and how do celebrities resonate with us?

The underlying thesis of this column has been that films are part of the psychological tapestry of the entire world, and it would follow then that celebrities are themselves part of this, key players in the grand narrative of culture that we play out in our artforms. Archetype Theory gives us one possible answer.

As I defined last week, the more expansive list of Archetypes used in marketing and storytelling represent a first level of differentiation of the deeper, Jungian archetypes. An equally important, second level would be demographical in nature — further defining the list of archetypes by gender, race, class, and cultural nationality. The next logical level would be the actualization of these archetypes as living roles, which would be the celebrities themselves. With the collusion of public and private life, any individual’s documented life becomes as much a part of the story they tell to the world at large as the movies they star in. Individually we might have some skill at separating the person from the role, but on a deeper psychological level it’s hard for the competing storylines not to share meaning with each other.

Stars then carry with them a variety of cultural meanings: archetypal, genre, aesthetic sensibility (including what we associate with quality). We subconsciously imprint this information on individuals, as though they contain the meaning of the stories they’re part of. When their real life colludes with this and there’s a disconnect between what they do and what we expect of them, they fall out of favor (or switch archetypal roles). When they’re in sync, we embrace them more. Consider the media narrative of somebody like Bill Murray or how we project a hidden, wounded depth onto Liam Neeson’s recent essentially two-dimensional action heroes based on his real-life losses.

“It is interesting that celebrities appear largely unaware of their part in the meaning-transfer process. Nowhere is this better illustrated than in their concern for typecasting. Actors say they dislike being cast repeatedly in the same role, claiming that typecasting limits their career and creative options. What they do not see is that their careers, their art form, and the endorsement process all depend upon typecasting, at least a mild form of it. The North American movie demands the participation of actors charged with meanings; it needs actors to bring their own meanings with them to a part. These meanings simplify the movie’s dramatic and expository task and give it substance and direction.” (Grant McCracken, Culture and Consumption II, 107).

Some actors seem to fit well within a cultural narrative that hangs an archetype on them. You can see this both in the way the public responds to them, and in the way that certain actors always seem to favor certain kinds of roles. The opposite is also true, and it’s little surprise that certain actors rebel against the roles our culture tries to burden them with. Elijah Wood, Daniel Radcliffe, and Shia Labeouf were all placed in roles representing the Innocent Archetype, and all rebelled in some fashion in their future cinematic roles, exploring cannibalism, bestiality, and violence among other things. It is hard to imagine that on a broad cultural level that is where we most want to see them, and so of course those projects would not bring along their old audience. Conversely, child stars like Natalie Portman and Jodie Foster played damaged Innocents when young, and so any next movie role brought with it symbolic redemption — and thus possibly more cultural embrace.

This means there is a grand collision of worlds in the culture at large — between the stories we tell, the meanings we project upon celebrities, and the real world actions that we then contextualize as a narrative. [3] A recent proof of that idea might be Matthew McConaughey’s transformation and success in the public sphere.

McConaughey built a career around a certain kind of role: the foolish but charming Southern “Good Old Boy.” While it gave him popular success, it certainly didn’t arouse critical interest. Now he’s playing the logical inversion of that type — still heroic, but somehow punished by the world (as reflected in his very physique) and wiser for it. That he found success with both, in different ways, implies that he has moved from one demographic’s interest to another’s. If archetypes speak for the culture as a whole, then McConaughey’s place within it is a part of that narrative. The last big cultural player to have a similar archetypal role was President George W Bush, whose self-created narrative moment of glory was to land on an aircraft carrier, wearing military regalia and declaring victory (for his father’s battle). Perhaps McConaughey’s recent turn is so appealing because it answers a larger public need, to see the next part of that archetypal story — the punishment and rebirth of that archetypal character — the fool who puts on the clothes of the hero, is punished for it, and becomes enlightened in his loss. [4]

There is certainly a negative aspect to celebrity, and one that is hard for its players on all sides. [5] But I do think that understanding that actors themselves portray and embody archetypes that resonate in the culture is a better, first basis for casting. While it’s hard to understand what archetype an unknown best embodies, it is much clearer with any actor who has had a degree of success. By making this the basis for casting decisions, you ensure that there is a direct connection between the actor’s audience and that of the story you are trying to tell — which may then better ensure the connection between celebrity casting, financing, and audience. [6]

Notes

1. Certainly, it is the only thing that William Goldman is willing to link definitely to a movie’s fortunes.

2. See the essay “Who Is the Celebrity Endorser? Cultural Foundations of the Endorsement Process” by Grant McCracken in Culture and Consumption II.

3. For the idea of history as a narrative, see the work of Jean-Francois Lyotard.

4. The ritualized sacrificing of the king — wherein a commoner is made the symbolic ruler, given all the riches of the realm, and then killed in a brutal ritual to regenerate the land — may be one of the grand cross-cultural narratives. It is presented by James Frazer’s The Golden Bough and also informs the work of Georges Bataille. I have not personally investigated whether their ideas sync with contemporary anthropological readings. That we may be enacting the same ritual on our children these days is my own take-away from this essay on school shootings by Robert Kurz.

5. Guy Debord in Society of the Spectacle: “The individual who in service of the spectacle is placed in stardom’s spotlight is in fact the opposite of an individual, and as clearly the enemy of the individual in himself as of the individual in others.”

6. Already there is some change in the relationship between celebrities, archetypes, and how that influences casting. In most of the Marvel movies, they have cast competent but lesser known actors because the characters themselves have more weight and draw than the actors playing them (superheroes being more obvious, primal archetypal characters than more dramatically-nuanced roles).

Previously: Archetype Theory

Next Week: Deep Metaphors

Nobody Knows Anything is a speculative journey through the more esoteric theories of popular culture: what that means, what comes next, and what can be done about it.

Charles Peirce is a screenwriter and musician, with an active interest in marketing, behavorial psychology and strategy. He finds it odd to talk about himself in the third person. He can be reached at ctcpeirce@gmail.com or via twitter @ctcpeirce.

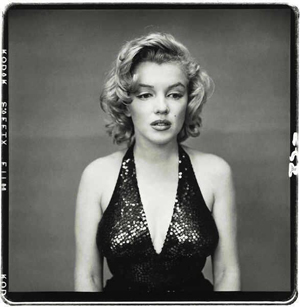

Marilyn Monroe photo by Richard Avedon, 1957.