It’s a pretty rare thing that a director has the opportunity to watch other directors at work. As a crew-member, I had a front row seat to almost every aspect of the job, pre-production through post. I never worked on a film that didn’t teach me something—whether it fell in the “to emulate” or “to avoid at all costs” column. These lessons helped me direct actors, assemble good crews, communicate effectively, have realistic expectations, and generally feel at home on a film set.

It’s a pretty rare thing that a director has the opportunity to watch other directors at work. As a crew-member, I had a front row seat to almost every aspect of the job, pre-production through post. I never worked on a film that didn’t teach me something—whether it fell in the “to emulate” or “to avoid at all costs” column. These lessons helped me direct actors, assemble good crews, communicate effectively, have realistic expectations, and generally feel at home on a film set.

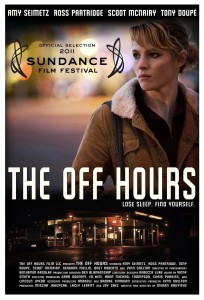

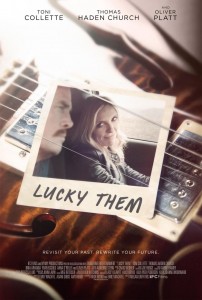

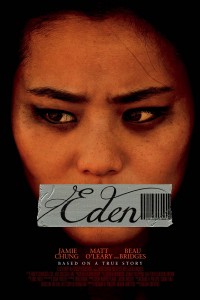

A little about me: In the past four years, I have directed three features (The Off Hours, Eden and Lucky Them) and been a co-, exec-, consulting, or straight-up producer on four others (The Catechism Cataclysm, Your Sister’s Sister, Koinonia and The Greens Are Gone). This recent uptick in creative productivity comes after a decade spent working below the line—first as a director of photography, then briefly an editor, then a 1st assistant director. Admittedly, much of the time I spent crewing was also spent longing for the day when I would be helming my own projects, but luckily I wasn’t so busy moping around that I missed out on all there was to absorb from working on other people’s films.

-

Give them what they need so that they can give you what you need.

Crews and actors don’t work in a vacuum. There is a collective goal in play at any given moment on a set, and in order to achieve that goal, people need information. The system is highly interdependent. Logging time on a variety of sets allows you to learn how departments run, what details people need to operate at their peak, and how to communicate that without pissing anyone off. The better you get at giving people what they need, the more you’ll find that they’ll provide the things that you need.

-

Watch and learn.

An underappreciated benefit of serving as an AD is that you have a front row seat to basically every aspect of the filmmaking process. You can listen in on conversations between all the key collaborators and watch what unfolds afterwards to see which methods of communication were most effective. I learned a lot from my vantage point, but here are a couple huge generalizations I noticed regarding communication: Actors respond to clarity, crews respond to decisiveness, and everyone responds to respect.

-

Hire people you trust, then trust them.

There are few things more annoying then being micromanaged. It undermines one of the most critical elements of a harmonious, productive environment: trust. If you don’t trust someone, don’t hire that person. Once you have lined up your team, give them some autonomy. When people feel ownership in the creative process they are more invested and their work reflects that.

-

You can create and curate your community.

When I began working in the industry, I ran face-first into the age-old clash of production vs. crew. This is the notion that there are opposing sides on a set, both of whom feel the other is taking advantage of them. As an AD, you are right at the heart of this battle. The only way to I found to fight this ideology was to disprove it, production by production, individual by individual. Good communities are built. It takes a commitment to fostering communication and open dialogue about what is working and what is not. It takes admitting you’re wrong once in a while and changing your ways. It takes the strength to address things directly and without emotion, with the common goal of making the set into a place where you want to be. Added benefit: once you know your community, you can curate your own sets to ensure the people you bring into your sacred production bubble are people who share your filmmaking philosophy.

When I began working in the industry, I ran face-first into the age-old clash of production vs. crew. This is the notion that there are opposing sides on a set, both of whom feel the other is taking advantage of them. As an AD, you are right at the heart of this battle. The only way to I found to fight this ideology was to disprove it, production by production, individual by individual. Good communities are built. It takes a commitment to fostering communication and open dialogue about what is working and what is not. It takes admitting you’re wrong once in a while and changing your ways. It takes the strength to address things directly and without emotion, with the common goal of making the set into a place where you want to be. Added benefit: once you know your community, you can curate your own sets to ensure the people you bring into your sacred production bubble are people who share your filmmaking philosophy.

-

Try to relax.

Over the years, I worked with many first time directors and found a pretty consistent common denominator lurking behind all bad choices: fear. Fear is the enemy of creativity. Feeling out of one’s element can be a huge distraction. Immersion helps. Working on a lot of sets helps you get comfortable in that environment and frees you up to focus on what you should be focusing once you are at the helm.

-

Treat people as collaborators, not employees.

Many directors and producers emanate the vibe that their crews should be subservient and/or grateful to be there. Pro tip: this approach does not instill dedication or passion for the work. Instead, it fosters a sense of obligation and erodes any sense of the communal creative experience that leads to great films.

-

The vibe on set translates to performances.

Imagine an environment where you are at your most productive and creative—somewhere you can truly bare your soul. Are there people yelling, texting and insulting each other all around you? I didn’t think so.

-

Set boundaries.

There are a lot of bitter people who work in film. Understandable—it’s easy to become bitter when you feel people are constantly working you to the bone and not appreciating your many sacrifices. The best way I’ve seen to sidestep this common trend is to set boundaries early and clearly. You may worry that you’re not being a team player, but I’d always rather have someone tell me up-front that they’re feeling taken advantage of than see it come out in the form of anger after the fact.

-

Barriers won’t just go away because you don’t like them.

It’s the nature of independent film that compromises have to be made. I’ve seen a lot of directors refuse to bend—cling to some unrealistic ideal until the very last second and then sulk when they inevitably must scramble to find another way. Look at the parameters of your schedule and your budget realistically as early as possible and figure out how to work within them while still protecting the heart of your film. If you don’t choose your own compromises others will impose them on you—and you probably won’t like their choices.

It’s the nature of independent film that compromises have to be made. I’ve seen a lot of directors refuse to bend—cling to some unrealistic ideal until the very last second and then sulk when they inevitably must scramble to find another way. Look at the parameters of your schedule and your budget realistically as early as possible and figure out how to work within them while still protecting the heart of your film. If you don’t choose your own compromises others will impose them on you—and you probably won’t like their choices.

-

No one is there to sabotage your film.

Something a lot of people seem to fail to comprehend is that everyone on set is there to get a film made—ideally a great one. When your AD or line producer asks you for information, they aren’t conspiring against you. They are trying to help make your film happen. Hiding information does not serve you. Be transparent. No one knows what you need unless you ask for it. You may hear no, but at least then a conversation can begin about how to achieve it some other way. You’re a director, be direct.

-

People want to work on good movies.

Contrary to popular belief, when the script is bad the crew knows it. And when they don’t feel any connection to the material, the job becomes about the paycheck. Most people got into this business in the first place because they love film. A good script—one that has been properly developed and made to be the best it can be—gives everyone a reason to show up each day and believe that they are part of something special. Not to mention that the better the script, the more access you have to those who are talented enough to be discerning.

-

Money is not the only resource.

My producers and I spent many years trying to raise money for The Off Hours before it dawned on us that it wasn’t the only path to getting the film made. We had all worked on the crew side for years and we had garnered a lot of goodwill in our community. You can’t just expect everyone to bend over backwards to fulfill your vision, but there are endless ways to make helping you something that helps them too—allowing them to step up to a key role, giving them good material for their reel, sponsorship possibilities, or even just the promise of you hiring them again in the future on a fully budgeted production. Find the win-win.

-

Don’t burn your investors.

A lot of things that happen on other people’s sets don’t have a direct impact on other filmmakers. Actors or crews have a bad experience and they attribute it to a specific production or set of people. Not so in the world of film finance. If those brave people who are willing to enter the risky world of indie film investment encounter a production that loses them thousands or millions of dollars, especially through negligence or poor management, they aren’t about to stick around and watch it happen again.

-

Feedback is good.

People who seal themselves away to complete their masterpiece will almost always end up with something that could’ve been way, way better. Seek out and embrace the opinions of others, ideally others who have no reason to please you or be kind. Wouldn’t you rather hear it from that random dude in a small screening room when you can still do something about it than read the same opinion printed in Variety for the whole world to see?

-

Things don’t sell for as much as you think.

I have been fortunate enough to share condos at film festivals with filmmakers who have sold highly buzzed-about films. What I learned: price tags are lower than you read about. It’s not the 90’s anymore. Reset your expectations and be aware of the market you are entering. This realization allowed us to finally move forward and make The Off Hours at a budget level that was much, much more responsible than the idealized version we had initially envisioned. Just because it’s what you want to make it for doesn’t mean it’s what you should make it for.

I have been fortunate enough to share condos at film festivals with filmmakers who have sold highly buzzed-about films. What I learned: price tags are lower than you read about. It’s not the 90’s anymore. Reset your expectations and be aware of the market you are entering. This realization allowed us to finally move forward and make The Off Hours at a budget level that was much, much more responsible than the idealized version we had initially envisioned. Just because it’s what you want to make it for doesn’t mean it’s what you should make it for.

-

Don’t burn bridges.

If you think there’s someone on your set who won’t affect the outcome of the project, or who will never end up in a position of power over you, who you can abuse with impunity, you’re wrong. You just are. You will be working with these people the rest of your career, if you’re lucky. Don’t be a dick.

-

People who succeed usually deserve it.

There are exceptions to this, of course, but generally speaking the people who succeed in the world of independent film work really, really hard. This goes for crews, actors, directors and producers alike. Working on other people’s sets is a reminder that nothing comes easily, but the opportunity to spend your days pursuing something you’re truly passionate about is worth fighting for.

Megan is a working filmmaker and a work in progress. Her latest film Lucky Them (starring Toni Collette, Thomas Haden Church, Oliver Platt and Johnny Depp) is available everywhere with a WiFi connection via VOD. Her film Eden (sometimes known as Abduction of Eden) is available online as well, and The Off Hours can be found through the film’s site. She also has a blog.

Megan is a working filmmaker and a work in progress. Her latest film Lucky Them (starring Toni Collette, Thomas Haden Church, Oliver Platt and Johnny Depp) is available everywhere with a WiFi connection via VOD. Her film Eden (sometimes known as Abduction of Eden) is available online as well, and The Off Hours can be found through the film’s site. She also has a blog.