So how can you stay true to yourself as a writer, especially when one is supposed to be imitating another writer’s voice? For one thing, one can stop chasing fads or writing what one think the showrunner might want to see. Jane Espenson, who has written for Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Battlestar Galactica and Game of Thrones and has also created her own Web TV show, Husbands, talks to me about how important it is to trust your own instincts and your own good taste. She is not the only one: Jenny Bicks encourages “writing what you want to write, going towards the love” and Tom Fontana goes as far as to very simply state that “being successful is being faithful to oneself.”

So how can you stay true to yourself as a writer, especially when one is supposed to be imitating another writer’s voice? For one thing, one can stop chasing fads or writing what one think the showrunner might want to see. Jane Espenson, who has written for Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Battlestar Galactica and Game of Thrones and has also created her own Web TV show, Husbands, talks to me about how important it is to trust your own instincts and your own good taste. She is not the only one: Jenny Bicks encourages “writing what you want to write, going towards the love” and Tom Fontana goes as far as to very simply state that “being successful is being faithful to oneself.”

Tom thinks that people often look to being successful as opposed to being faithful: “And when I say faithful, I mean faithful to themselves and to the truth within them. And I think it’s very easy for that to get lost in the need to be successful, in the ‘Oh, I want the trophies, I want the money, I want the car, I want the house’ way. And I only say that having been seduced by that and then having woken up and said, ‘Well, wait a minute, is that really what I wanted out of being a writer?’ ” Tom talks about how he probably could have had a more successful career and how there were several times when he chose to not do what was commercially the wisest choice. He feels like he has been continually faithful to his writing, though, and because of that, he doesn’t feel the need to be successful in his career in a traditional way (although, of course, he is that, too).

I ask him whether he thinks that being faithful is also possible if a writer is supposed to be writing in another writer’s voice, the showrunner’s. His answer is illuminating: “What I always say to the writer is, ‘With the first draft you teach me how to write this show. With the second draft I’ll teach you how to write this show.’ So I want them to feel totally free to try anything they want.” He explains how some showrunners make the mistake that they tell another writer how they would have written the script. “My whole thing is, I don’t say, ‘this is what I want,’ because if you say to another writer ‘this is what I want,’ that’s what you get, and I don’t want to be handed back scenes which I could have written myself.”

An issue that is directly connected with the issue of rewriting is writing credit. If more than one writer is involved in the writing of one episode, who should be credited? Terence Winter makes it very clear that he considers rewriting, where necessary, part of his job as the showrunner and head writer, and that he is therefore not overly friendly toward the idea of taking credit for it – whoever was assigned the script initially, their name stays on it. “I’ll only put my name on scripts that I write in their entirety from the beginning,” he says. But obviously showrunners are split about this. There are showrunners who feel that if they rewrite more than 50% of a script, they should definitely be putting their name on it.

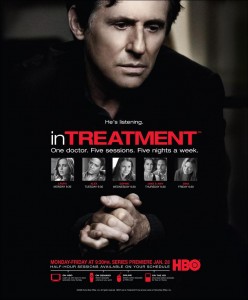

For Warren Leight, who has the showrunner on In Treatment and Lights Out, but also on Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, there’s no relationship between who writes what and how credit is determined in TV: “It’s a very bad credit system we have. Obviously, in a writers’ room system everyone is pitching in on everyone’s episode and sometimes the only way justice can be done is to distribute credit evenly.” Again, matters are in the hands of the showrunner. Warren explains how he will try to reward the people who work harder with a little more credit as the season goes on. “But there are people who only care about credit and that kills you,” he adds.

For Warren Leight, who has the showrunner on In Treatment and Lights Out, but also on Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, there’s no relationship between who writes what and how credit is determined in TV: “It’s a very bad credit system we have. Obviously, in a writers’ room system everyone is pitching in on everyone’s episode and sometimes the only way justice can be done is to distribute credit evenly.” Again, matters are in the hands of the showrunner. Warren explains how he will try to reward the people who work harder with a little more credit as the season goes on. “But there are people who only care about credit and that kills you,” he adds.

Everyone who has rewritten someone else’s screenplay knows how difficult it is not to change more rather than less and to not have the feeling that one has had to rewrite everything. Rewriting is a tricky business. On the one hand it is easier than writing because one does not

have to face the blank page. On the other hand it needs a lot of sensibility and capability to be able to rewrite and not create a new draft – with its very own first draft problems. Jane Espenson says it as clearly as possible: “As a writer, I like to hear my words. As a showrunner, I like to hear my words. So I probably rewrite a little more as a showrunner than writer-me would like.” But, as she says, the show is not there to give the writers a chance to hear their words, the writers are there to serve the show and the showrunner.

Next Up: Post #8: The Real Secret of Success of American TV

If you are interested in reading more, including the full interviews on their process as writers with creators such as Terence Winter, Tom Fontana, Warren Leight, Robert Carlock, Janet Leahy and many more, you can purchase the book Inside the Writers’ Room. Conversations with American Writers here.

Christina Kallas has written and produced several feature films and TV shows in Europe before she relocated to New York in 2011, where she is currently teaching at Columbia University’s and Barnard College’s Film Programs, and editing her next feature film (and her first as a director,) 42 Seconds of Happiness. She is the author of six books in her three writing languages, including the above book as well as Creative Screenwriting: Understanding Emotional Structure (London/New York, 2010). Most recently, she was honored for her outstanding contribution to the international writers’ community in her eight years of tenure as President of the Federation of Screenwriters in Europe. You can reach her at improv4writers@gmail.com and follow her on Facebook or Twitter and join the Writers Improv Studio group page for updates.

Christina Kallas has written and produced several feature films and TV shows in Europe before she relocated to New York in 2011, where she is currently teaching at Columbia University’s and Barnard College’s Film Programs, and editing her next feature film (and her first as a director,) 42 Seconds of Happiness. She is the author of six books in her three writing languages, including the above book as well as Creative Screenwriting: Understanding Emotional Structure (London/New York, 2010). Most recently, she was honored for her outstanding contribution to the international writers’ community in her eight years of tenure as President of the Federation of Screenwriters in Europe. You can reach her at improv4writers@gmail.com and follow her on Facebook or Twitter and join the Writers Improv Studio group page for updates.