By Christina Kallas

So should we be discussing TV series as nothing less than long cinematic narratives? And if so, what would that mean? It is fair to say that TV, just half the age of film, has only recently (perhaps in the last 15 years) come into its own. Writers have only recently learned to take advantage of the unique powers of the medium itself. For years the focus was on each episode being a complete story, a standalone. Not only in procedurals but in series generally, the dramatic focus was on the unit of the episode. A TV episode was a mini-movie (much as a web episode is a mini-TV episode now). Then the primary canvas of the TV medium became the season.

So should we be discussing TV series as nothing less than long cinematic narratives? And if so, what would that mean? It is fair to say that TV, just half the age of film, has only recently (perhaps in the last 15 years) come into its own. Writers have only recently learned to take advantage of the unique powers of the medium itself. For years the focus was on each episode being a complete story, a standalone. Not only in procedurals but in series generally, the dramatic focus was on the unit of the episode. A TV episode was a mini-movie (much as a web episode is a mini-TV episode now). Then the primary canvas of the TV medium became the season.

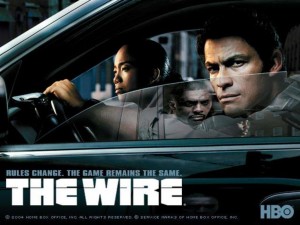

Today’s TV writers think of their shows and develop their stories and characters, using the season or even the whole series as dramatic unity. Sometimes they even refer to them as “visual novels,” where the first episodes of the show have to be considered much as the first chapters of a book. “Think about the first few chapters of any novel you ever liked, say, Moby-Dick,”

writes David Simon in his 2004 book The Wire: Truth Be Told.“ In the first couple chapters, you don’t meet the whale, you don’t meet Ahab, you don’t even go aboard the Pequod. All that happens is you go with Ishmael to the inn and find out he has to share a room with some tattooed character. Same thing here. It’s a visual novel.”

In recent years scholars and critics have increasingly used the term “quality TV” to describe TV series which have attracted particular critical claim. This implies that some TV shows are of higher quality than others, which is, of course, a purely subjective evaluation and therefore has little academic merit. Robert J. Thompson attempted a definition of the term in his 1997 book Television’s Second Golden Age: From Hill Street Blues to ER, which actually precedes the creation of the series now often described as “quality TV”: “It must break the established rules of television and be like nothing that has come before. It is produced by people of quality aesthetic ancestry, who have honed their skills in other areas, particularly film. It attracts a quality audience. It succeeds against the odds, after initial struggles. It has large ensemble cast, which allows for multiple plot lines. It has memory, referring back to previous episodes and seasons in the development of plot. It defies genre classification. It tends to be literary. It contains sharp social and cultural criticisms with cultural references and allusions to popular culture. It tends toward the controversial. It aspires toward realism. Finally, it is recognized and appreciated by critics, winning awards and critical acclaim.”

Another interesting term which emerged in the 2000s is Kristin Thompson’s “art television” – derived from the more familiar term “art cinema,” which also presupposes subjective evaluation. In her book Storytelling in Film and Television Thompson in particular compares David Lynch’s film Blue Velvet with his television series Twin Peaks and argues that US television shows which are “art television,” such as Twin Peaks, have “a loosening of causality, a greater emphasis on psychological or anecdotal realism, violations of classical clarity of space and time, explicit authorial comment, and ambiguity.” Thompson claims that series such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer, The Sopranos, and The Simpsons “have altered long-standing notions of closure and single authorship,” which means that “television has wrought its own changes in traditional narrative form,” while The Simpsons use a “flurry of cultural references, intentionally inconsistent characterization, and considerable self-reflexivity about television conventions and the status of the programme as a television show.”

Whether we adopt one or both of the terms suggested above or indeed propose new ones such as the one I am proposing (LCN or Long Cinematic Narrative,) which admittedly also does not escape the dangers of subjective evaluation (who shall define what is cinematic?), one thing is clear: the TV series we are talking about seem to have common characteristics that can also be found in films of alternative structure – as opposed to films of classic structure or, in Thompson’s words, “traditional narrative forms.” They are, for instance, characterized by multi-protagonist stories which overcome the hierarchical organization reflected in our classic storytelling’s privileging of one character and his or her point of view over the rest (multiple narrative threads, large ensemble of characters,) by the replacement of the principle of causality with the principle of synchronicity (elimination of formalist explications for cause and effect, violations of classical clarity and unity of time and space, ambiguity,) and by a programmatic desire to represent emotional truth, however complex it may prove to be (realism, ambiguity, defiance of genre classification.)

Whether we adopt one or both of the terms suggested above or indeed propose new ones such as the one I am proposing (LCN or Long Cinematic Narrative,) which admittedly also does not escape the dangers of subjective evaluation (who shall define what is cinematic?), one thing is clear: the TV series we are talking about seem to have common characteristics that can also be found in films of alternative structure – as opposed to films of classic structure or, in Thompson’s words, “traditional narrative forms.” They are, for instance, characterized by multi-protagonist stories which overcome the hierarchical organization reflected in our classic storytelling’s privileging of one character and his or her point of view over the rest (multiple narrative threads, large ensemble of characters,) by the replacement of the principle of causality with the principle of synchronicity (elimination of formalist explications for cause and effect, violations of classical clarity and unity of time and space, ambiguity,) and by a programmatic desire to represent emotional truth, however complex it may prove to be (realism, ambiguity, defiance of genre classification.)

Perhaps writing for the screen is the literary form that corresponds most to how we perceive the world today, and perhaps the TV screen and its long form narrative are the best expression of such perception. Indeed, in the last decade or two, the great explosion of cinematic narrative complexity seems to be gravitating more and more towards TV and less towards the movies – possibly, among other reasons, because there are only so many threads and subtleties you can introduce into a two-hour film, but also because TV is traditionally more of a writer’s medium and so perhaps more of a home to sophisticated writing.

Next Up: Post #4: New Patterns of Attention (and Addiction)

If you are interested in reading more, including the full interviews on their process as writers with creators such as Terence Winter, Tom Fontana, Warren Leight, Robert Carlock, Janet Leahy and many more, you can purchase the book Inside the Writers’ Room. Conversations with American Writers here.

Christina Kallas has written and produced several feature films and TV shows in Europe before she relocated to New York in 2011, where she is currently teaching at Columbia University’s and Barnard College’s Film Programs, and editing her next feature film (and her first as a director,) 42 Seconds of Happiness. She is the author of six books in her three writing languages, including the above book as well as Creative Screenwriting: Understanding Emotional Structure (London/New York, 2010). Most recently, she was honored for her outstanding contribution to the international writers’ community in her eight years of tenure as President of the Federation of Screenwriters in Europe. You can reach her at improv4writers@gmail.com and follow her on Facebook or Twitter and join the Writers Improv Studio group page for updates.

Christina Kallas has written and produced several feature films and TV shows in Europe before she relocated to New York in 2011, where she is currently teaching at Columbia University’s and Barnard College’s Film Programs, and editing her next feature film (and her first as a director,) 42 Seconds of Happiness. She is the author of six books in her three writing languages, including the above book as well as Creative Screenwriting: Understanding Emotional Structure (London/New York, 2010). Most recently, she was honored for her outstanding contribution to the international writers’ community in her eight years of tenure as President of the Federation of Screenwriters in Europe. You can reach her at improv4writers@gmail.com and follow her on Facebook or Twitter and join the Writers Improv Studio group page for updates.