By Charles Peirce

It would seem, to the eyes of Hollywood, the high form of film has become the franchise. It satisfies the two poles of conventional business wisdom: limiting risk as it promises more of the same, maximizing profit as it entices investors with that self-same prospect.[1] The Hobbit is stretched out to encompass three movies, hordes of young adult novels are on the horizon, and Bob Iger suggests Frozen will now be a franchise after its huge success, but it’s hard to imagine that wasn’t always the plan. Strangely, though, two of the pioneers of the form, George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, both predict doom for what they helped create. And the recent failure of The Lone Ranger (and John Carter before that) suggest they might just be right.

It would seem, to the eyes of Hollywood, the high form of film has become the franchise. It satisfies the two poles of conventional business wisdom: limiting risk as it promises more of the same, maximizing profit as it entices investors with that self-same prospect.[1] The Hobbit is stretched out to encompass three movies, hordes of young adult novels are on the horizon, and Bob Iger suggests Frozen will now be a franchise after its huge success, but it’s hard to imagine that wasn’t always the plan. Strangely, though, two of the pioneers of the form, George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, both predict doom for what they helped create. And the recent failure of The Lone Ranger (and John Carter before that) suggest they might just be right.

It’s hard not to be cynical about this, or exhausted by it, or feeling the need to join the chorus that says serious work is on television now rather than in the theatre. There used to be an idea that sequels in general were always bad, with the exceptions only proving the rule, as once lampooned in Scream 2. But now, any success brings the threat of a sequel, even if it’s only an undistributed knockoff whose only relationship to the original is in the name. One side seems to want franchises at any cost, the other to abhor them. Perhaps they seem so aggressive and intolerable because they are essentially cultural monopolies in an era with relatively de-centralized media control.

But maybe it’s always been that way. If you’ve been following this column so far, then you know that one of its main ideas is that film is an expression of culture as a whole, and that its successes, failures, and obsessions are a reflection of our individual desires, en masse. From that perspective, every film is a sequel and every large success is, indeed, the possibility or desire for a franchise.

We tend to think of sequels as repeats of the same, the same characters in slightly new situations, so it’s not suprising they would reach a terminal point of interest. Chiefly, we want our stories to evolve, their characters to change and grow, learning new lessons. Highstakes dramatic writing calls for just that, built as it is around major reversals, with its characters to become their opposite, innocents into heroes and villains into saviors. But the business minds behind sequels shy away from this, fearing that changing a character significantly will lose whatever created their appeal in the first place. There are exceptions — Harry Potter did a masterful job of allowing its characters to grow at the same pace as its audience (at least in the books), and Michael Arndt talks about how he wrote Toy Story 3 from the perspective of a child’s changing relationship as he grows up. Star Wars has also done this, though seemingly with less intentionality. [2] Indie Film has also had its successful sequels of this nature — Kevin Smith’s Clerks films and Before Sunset / Before Sunrise / Before Midnight quickly come to mind. Other sequels have offered less change, adhering tightly to their internal formulas, and perhaps their diminishing appeal is based on this failure to evolve with their audience and tell them the desired next part of the story.

If you think of sequels only in terms of the purely primal, symbolic components of the stories they tell, rather than their trappings, larger interesting trends start to take shape. A set of the particularly successful recent classics of science-fiction form an interconnected thematic narrative over time, showing both our anxieties and fears about technology, computers, and the divide between being alive and creating life. Consider Blade Runner, the first two Terminator movies, and the original Matrix as though they were part of one larger story. Although all originate from separate sources and contain separate worlds, they’re clearly grappling with a bigger issue we’re still in the infancy of tackling. I would suspect that the next science-fiction film that has a major impact on audiences (culturally and financially) will continue this precise narrative.

Currently, comic books are where we see one of the biggest successes in franchises, and it shouldn’t come as a surprise. I don’t think it’s because technology finally enables them to be realized with more realism, or that they appeal particularly well to children and younger adults alike, or that they’ve allowed a shift away from financing based on celebrity to financing based on character [3] — rather it’s because superheroes represent some of the oldest modern franchises, with characters that have been around for almost a century now, proving over time their validity (and flexibility) as resonant archetypes for the culture at large.

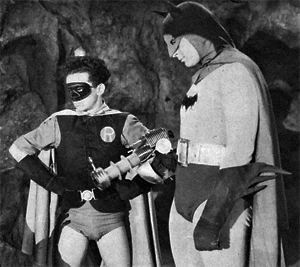

Most people think that Batman’s live-action existence started with the campy 60s television show, but Batman had several incarnations and movie serials long before that. That Batman has so well stood the test of time and allowed such a wide variety of interpretations — from silly pop art to Christopher Nolan’s post-9/11 stormtrooper — isn’t a coincidence. Batman started in the comics in 1939, but even then he was a pastiche of pre-existing cultural archetypes. Depending on which aspects of the character you focus on he can be traced back — to Zorro; to Louis Feuillade’s Judex [4]; to the transgressive genius of Maldoror and the gothic literature of The Monk; to the celebrity criminal Lacenaire; to Robin Hood; to the antagonistic and immoral puppet Punch; to the defiant clown who is the only one permitted to challenge the king; and onwards.[5] The outlaw that has to take the law into their own hands — defying the ruling order to create justice — is a primal archetype throughout our history.

Most people think that Batman’s live-action existence started with the campy 60s television show, but Batman had several incarnations and movie serials long before that. That Batman has so well stood the test of time and allowed such a wide variety of interpretations — from silly pop art to Christopher Nolan’s post-9/11 stormtrooper — isn’t a coincidence. Batman started in the comics in 1939, but even then he was a pastiche of pre-existing cultural archetypes. Depending on which aspects of the character you focus on he can be traced back — to Zorro; to Louis Feuillade’s Judex [4]; to the transgressive genius of Maldoror and the gothic literature of The Monk; to the celebrity criminal Lacenaire; to Robin Hood; to the antagonistic and immoral puppet Punch; to the defiant clown who is the only one permitted to challenge the king; and onwards.[5] The outlaw that has to take the law into their own hands — defying the ruling order to create justice — is a primal archetype throughout our history.

Archetypes and Archetype Theory are something I’ll discuss in depth in the future, but many of our stories (if not all of them) are centered around characters and ideas that align very successfully with that idea. Archetypes are always going to resonate, but culturally our relationships to them change over time. The Outlaw Archetype has been “trending” for some time now, in everything from the likes of Batman to Breaking Bad to Sons of Anarchy to Orange is the New Black, perhaps so appealing because our larger cultural dialog about the Hero or Ruler Archetype has become fractured and complicated.

With that in mind, the recent failure of The Lone Ranger might have entirely different causes than the business risks of the franchise form. All of Johnny Depp’s larger “franchise” roles have featured him essentially playing the same archetypal character. Regardless of name, characterization, or the setting of the movie, Jack Sparrow in The Pirates of the Caribbean movies, his Mad Hatter in Alice in Wonderland, even his Barnabas in Dark Shadows, have all been of the Trickster Archetype. It’s a role he often portrays, but it might not be appealing at this moment to the popular psyche (which again may just be rooted in something like our current relationship to our government and financial institutions and issues of privacy and transparency). From an archetypal perspective, The Lone Ranger movie married the archetype of the Trickster (Depp’s version of Tonto) with that of the Fool (The Lone Ranger himself) precisely at a time when audiences are looking toward the Outlaw archetype for meaning (which the Lone Ranger originally embodied). If you accept that idea, then it’s not whether the movie was particularly good or bad as these things go, it’s that it no longer offered what audiences wanted or needed in the primal, psychological narrative of cultural storytelling.

I do not personally think that the current form of franchises will fail — I think their financial structures are too labyrinthine and well designed. Furthermore, I think that regardless of your relationship to franchises, it is important to consider that their success is not entirely engineered — that their appeal comes because they are, at the moment, the major narratives of our culture. They may be infantile, simplistic in their characters and stories, trying to entice the most with the least, but that in itself is part of their changing relationship within our society. Franchises and sequels are going to continue happening, the idea is to see them as larger pieces of an interconnected narrative that helps us explore and know the world and ourselves. Storytelling is a continuation of all the stories that have come before, part of everything you have learned and known to date. It’s a grand tradition whose very meaning comes out of its evolution. We shouldn’t fear that idea but instead figure out how to help it grow as we do.

Notes

1. While it’s not hard to understand the appeal of a franchise from a purely business perspective, it is still import to remember that they are not all built the same.There’s a great deal of business difference between a Marvel studios movie (who owns all of the associated characters), a Spiderman movie (where Sony owns the film rights and doesn’t want that license to lapse), or a Superman or Batman movie. Or a Transformers, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, or Battleship movie (all owned by Hasbro). Or Avatar. Or The Hunger Games. Or Harry Potter.

2. Consider also how the generations who grew up with the original Star Wars trilogy were given a narrative about a young man who learns his father is a villain and manages not only to resist his ways but also to redeem him (all in a universe that seems to embrace a spiritual causality and is populated with stark aesthetic minimalism and vast empty spaces). Whereas the generation that was raised with the new trilogy has a story about a young man who gives into his basest urges and becomes evil, in a universe overbrimming with color and variety, and where everything — even the Force — has a scientific explanation.

3. I suspect Robert Downey Jr’s pricetag was one of the few but significant mistakes Marvel made with their franchise model.

4. Judex is a costumed detective created in 1916 who fights crime from his secret lair. Feuillade also created Fantomas, the sinister supervillain / terrorist who has seen a large variety of cultural permutations over time, including my personal favorite Danger Diabolik.

5. Some of these historical links help to clarify why The Joker is the necessary other side to the Batman mythology.

Previously: What Makes A Film Successful?

Next Week: Rethinking Transmedia and Crossmedia

Nobody Knows Anything is a speculative journey through the more esoteric theories of popular culture: what that means, what comes next, and what can be done about it.

Charles Peirce is a screenwriter and musician, with an active interest in marketing, behavorial psychology and strategy. He finds it odd to talk about himself in the third person. He can be reached at ctcpeirce@gmail.com or via twitter @ctcpeirce.