By Colin Brown

For 15 months now the independent film world has been eagerly awaiting the regulatory fine print on the JOBS Act that many believe will both broaden and quicken their fundraising efforts across the U.S. Now that the SEC has finally published those first rules that allow filmmakers and film startups to advertise their investment proposals to the public, some will have been intrigued by a new amendment that specifically disqualifies bad actors.

Before film critics all rise up in celebration, let’s be clear that America’s financial watchdog is not about to outlaw scenery-chewers, hams, stilted amateurs and all those glorious Raspberry Award winners from being pitched to millionaires. There would be too little film industry left to regulate. But the “bad actors” referred to here will be just as familiar to anyone who has done enough time in the film market trenches: financial miscreants.

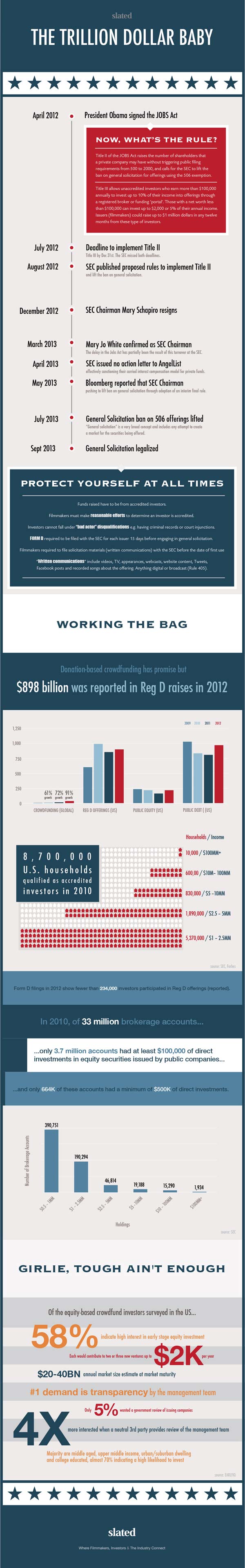

Felons and those “subject to court or administrative sanctions for securities fraud or other violations of specified laws” will be barred from participating in private placements under Rule 506 of Regulation D – the exemption through which at least $898 billion in total equity and debt capital was raised last year, including the majority of American independent films seeking private money. This new bad actor prohibition, hard as it is to believe it wasn’t in place already, has to be welcomed despite the added burdens it will place on fundraising starting this September.

Why? Because even if the SEC’s final rules don’t end up inducing millions more private investors overnight into the film industry, they will still spur the need for more diligent background checks, not to mention private placement memos that are grounded in more realistic and informed financial projections. The demand for better film data and verification paperwork will increase, and so too the likelihood that this industry will win acceptance and long-term legitimacy among a wider pool of accredited investors.

There are 8.7 million such high net-worth individuals and institutional investors in the U.S., reckons the SEC, and yet only 234,000 of them participated in Reg. D offerings of any stripe last year. This compares to 3.7 million brokerage accounts that have at least $100,000 invested in shares of publicly listed companies. As paltry as that percentage is of accredited investors who made a recent friends-and-family or angel investment in a business startup, an even tinier handful will have even considered film as a bona fide option. Despite a growing recognition that the film business shares many of the same risk/reward characteristics of Silicon Valley’s tech ventures, film is saddled with popular misconceptions. Ask a room full of investors, as I have done, whether they would rather stake $10,000 on the next prospective Facebook or support a would-be Paranormal Activity and the majority will gladly say Facebook – even though, statistically speaking, the chance of landing either outlier has been put at no better than 5%. When it comes to film it seems investors have trouble seeing past the probability of failure.

How far the new Title II of the JOBS Act will help redress that imbalance by invigorating film investing is open to conjecture, especially since the SEC may introduce further refinements over the next 60 days. In the immediate aftermath of last week’s ruling, legal experts such as Morrison & Foerster wondered whether the compliance issues were potentially cumbersome and ambiguous. As it stands, fundraisers must make “reasonable efforts” to verify that their investors are indeed “accredited”, a process that could include reviewing two years of tax returns, and relevant bank statements and credit reports. The SEC is also applying a “did not know, and in the exercise of reasonable care, could not have known” standard of diligence for companies identifying potential bad actors. Both requirements, while laudable in their intentions, could prove nettlesome in practice – and a boon for intermediaries willing to shoulder those responsibilities on film’s behalf.

But those are relatively minor legal hoops compared to what has been made permissible. Film producers may not have been aware of this but they have been subject to Depression Era securities laws that essentially prevented from promoting their projects to the investment world at large. No matter how large their LinkedIn networks happen to be, they have been obliged to call all potential backers individually. Soon they will be able to broadcast their offerings to anyone that cares to listen, although they can only take money from the officially wealthy. Soon you’ll be able to pitch not just your local dentist but also all dentists right across the country. For both film projects and film-related startups this opens the door to small-check investments on a scale previously impossible.

Those who think the floodgates have just been opened to fraud need only look over the border to Canada. There, in every province outside Ontario, crowdfunding for equity has been legal for several years. Interestingly, the biggest challenge that the Vancouver startup scene faces is not so much in weeding out the unscrupulous, but in getting noticed in the first place. As VentureBeat recently noted: everyone in British Columbia can potentially invest, but most don’t even know that they can.

There is a lesson here for the US independent film industry now poised to market their projects across the nation. Before engaging in a crowdfunding free-for-all, some collective thought should be given on how best to solicit this new investor base. Unless we find ways to market the very concept of film investing, and how crowdfunding can benevolently play into that, it will be the good actors that end up being disqualified.

Editorial Director of Slated