By Julien Favre

With the world economy on the brink, the current environment has rarely been so tough for independent filmmakers. To get our films made and, even more so, to see them sold and/or distributed, is getting incredibly challenging. Foreign sales estimates for low budget independent films are a tenth of what they used to be pre-2008, and let’s not be fooled by the numbers. We will be happy if we sell at all, even for symbolic numbers. From a filmmaker’s perspective, we have entered a dichotomous world: a shrinking pool of independent films do well; most don’t make any significant business. It is now as if there is only room for one indie hit per year. If you are not that film that everybody wants, you barely exist and your business footprint will be close to zero.

Now, you can look at this situation in two different ways. One way is to adjust to the market and give it what it wants, or can economically bare. This means making genre films that still have somewhat of a market and will recoup as long as they are technically sound and are made for the right price. You can also continue to make “art house” films (for lack of a better word) as long as you don’t spend more than $80,000 making them, since this is what you can realistically hope to net from world wide sales if the film turns out okay and has a decent festival run.

But the other way to look at these dire market conditions is to ask ourselves: does the world really need another decent film? The elephant in the room is that most films are bad or average. Back when the economy was strong and there was a theatrical and DVD market for indie films, decent films used to do well enough to justify the venture from a business standpoint, but not anymore.

Even if no filmmaker or producer sets out to make yet another average film, we would be lying to ourselves if we were claiming that we never went in production on a film knowing full well that the script needed another pass, or praying that an average director would turn a good script into a great film, or that we would be able to cut around bad performance.

But the reality is that there is no room for average films anymore. There isn’t even much room for good movies unless they are backed by heavyweight distributors. We can lament about how unfair, how scandalous it is that our labour-of-love films don’t sell and nobody sees themt. Or we can accept the reality of the market and raise the bar of what we produce.

A month or so ago, someone asked me WHY i was a producer. I am so used to people asking me WHAT a producer is, but I was taken aback by this very simple question, and I didn’t know what to say. Producing is so much part of me that I cannot contemplate doing anything else, but that doesn’t answer the question.

But I realized after the fact that the WHY question is fundamental, and even more so considering the difficulties the indie film world is facing today. Since we are certainly not doing it for the money (and in most cases unfortunately not even for our investors’ money), then why are we doing it? Not for the hours, obviously. Producing is not the healthiest or stress-free occupation. And from a human standpoint, it is rarely satisfying either. As a function of what we do, we are at the receiving end of all grievances and rarely get any recognition when things do go well because, you know, all is normal then…

So why are we doing it?

Because there is nothing like the experience of watching an amazing film and being devastated, blown away, changed by it. For me, it started with Akira Kurosawa’s Ran. I remember being unable to speak for the rest of the day, and trying to find a way to merge with that world, keep it alive in my head, escape in it.

So deep down, this is what has been driving me: I want to hurt the audience with beauty, emotionally wreck the viewers by exposing them to true art. This is the WHY. This is why I want to make movies. But I guess this is very easy to lose sight of this as we struggle with the reality of the business, and making a living, and deal with the pressure of “producing something” to justify being a producer.

In an oft-quoted letter to his friend Oskar Pollak, Franz Kafka wrote: “I think we ought to read only the kind of books that wound and stab us. If the book we are reading doesn’t wake us up with a blow on the head, what are we reading it for? …we need the books that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone, like a suicide. A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us.”

Of course, creating truly great art is incredibly difficult, and depends on so many factors, most of them beyond our control as producers. It is likely beyond most producers’ or filmmakers’ ability actually. There are plenty of competent people, but true talent is scarce. And even with the best intentions, the highest artistic integrity, there is never any guarantee of success.

But our responsibility, more than ever, is to try, to be intransigeant with content, to look at our slate with a cold heart and ask ourselves: does this movie really need to be made? And why? Would I honestly go see it if I wasn’t the producer? It is so hard to get something made that making something, anything, seems like an achievement in itself. But it is not good enough, not anymore.

And in answering these questions, let’s be honest. If what we read is not truly great, not really original, not inspired, if the demo-reel we are watching is average, if the ending doesn’t quite work, let’s keep working, let’s keep writing, let’s keep looking for the right creative partners and the right elements.

So rather than lament the lack of opportunities, our response as producers to these dire times should be to try and make better films, make great films, not just good ones. Films that will get seen, and distributed, regardless of the market conditions, the weather, venus’ transit or what other movie is being released that week.

There is no room for good anymore, but simply making good movies is not why we got into this anyways, so maybe this is our opportunity to become who we always wanted to be, and do what we always aspired to: make films that break the frozen sea inside.

Julien Favre is a producer at DViant Films, an independent film company based in Los Angeles and Toronto. The company’s latest release, Martin Donovan’s Collaborator, opens at the Egyptian in Los Angeles this Friday.

COLLABORATOR opens theatrically in Los Angeles tomorrow (Friday, July 20th) for a limited one week run. Screening times here.

As of this writing COLLABORATOR is 82% “Fresh” at Rotten Tomatoes.

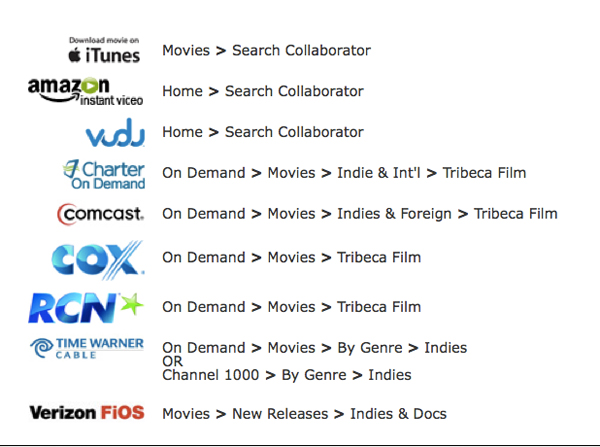

How To Watch Collaborator: